Given the number of old churches that show up on this website, you might think I’m Catholic. I’m not – I’m not even conventionally religious -- so why do I love the ancient basilicas and medieval abbeys scattered across the landscape of the deep heart of France? I found myself thinking about that question again when I parked a few blocks away and made my way through a dense leafy walkway to the great abbey of Mozac.

It’s surrounded these days by houses and school buildings, so your imagination has to work overtime to reconstruct what this place must have been like at its origins. (The whole town is now folded in as a suburb of Riom.) As I made my way through the old church, though, I reflected on four specific things I think make places like this so moving and important to me:

(1) The Mozac abbey is breath-takingly OLD

It’s so old, in fact, that the exact date of its founding isn’t known. Some sources say it was started around 535 C.E., but I’ll go with the abbey’s own estimate – around 680 C.E., when a bishop named Calminius came carrying a fragment of St. Peter’s skull given to him by the Pope to launch a new site here. (He was a serial founder, having already launched two other abbeys -- Laguenne (in Corrèze) and the Monastier-Saint-Chaffre (Haute-Loire)).

When I visit a place this old, I like to put some effort into thinking about what was going on in the world around Calminius. Historians these days are reluctant to use the old term “Dark Ages” because it sounds pejorative and civilization was in a high state of evolution during the period – but as far as the blank spots in the historical record go, it’s still a fair characterization, I think.

And the year 680 fits exactly into that hole in western history: just after the fall of the Roman empire, just after King Arthur supposedly defended a corner of “England” from the Saxon invaders. (There wasn’t really an “England” yet – or a “France” or “Germany”, just a jumble of fractious little kingdoms whose names are about all that remains of them now.) Caliminius came to Mozac before Muslim armies conquered Spain, a century before Charlemagne started making his influence felt in the territories that are now western Europe.

Caliminius’ own story is so clouded in the fog of lost records and legend-building that it’s hard to say much about him with certainty. He was likely part of a Roman family that had moved to the area around Clermont-Ferrand. Medieval historians later credited Calminius with some honorific titles like “Senator of Rome” and “Duke of Aquitaine” and “Count of Auvergne”, but since the Aquitaine and the Auvergne didn’t really exist as recognizable entities in the 7th century, these titles seem hard to believe. He’s venerated in the Catholic tradition today under the name of Saint Calmin.

(2) Mozac has ties to great movements in western history

And although the abbey at Mozac was in a very remote, isolated part of the Auvergne, it was in many ways on the front lines of the chaotic struggle for political and religious dominance that was going on across the continent. Even into the 800s and 900s C.E., Christianity was not a “given” to win the hearts and minds of people living in Europe – there were constant challenges from Islamic armies, widespread adherence among the locals to pagan traditions, a contentious split between East and West within the Christian church, and heresies multiplying within the Western church.

As Derek Wilson puts it in his short biography of Charlemagne (who, remember, was still almost 100 years in Calmin’s future!),

“With all these internal weaknesses and external pressures, no betting man would have wagered on the emergence from this threatened culture of a world-conquering Christian civilization.”

So that was the world – chaotic and uncertain -- in which Saint Calmin operated, the world in which he founded this order at Mozac. He and his successors persisted in the struggle, though, and over time, two major events secured the future of his abbey:

- In 848 C.E., King Pepin II of Aquitaine gave Mozac the relics of Saint Austremoine, one of the very first missionaries to visit these parts and the first Catholic bishop of the Auvergne (around 250 C.E.). Austremoine’s bones are contained in a painted wooden 16th-century chest on display in the church and decorated with images of the 12 Apostles and Saint Benedict. The presence of these important relics made Mozac a major pilgrimage site.

- Pope Urbain II came to nearby Clermont in 1095 C.E. – a visit which altered the flow of world history when he gathered the knights of France in a field to declare the First Crusade to Jerusalem. While he was there, though, he took the opportunity to create a formal tie between Mozac and the great network associated with the Abbey at Cluny, the vastly influential institution that helped consolidate Christian practice across France and western Europe

(3) The abbey is an important example of medieval architecture

This powerful new association with Cluny required a great new church – the one you see here now. Like so many other 10th- and 11th-century churches in the deep heart of France, it’s built in the Romanesque style. I love sitting in these shadowy old buildings, admiring the feats of engineering and art required to make the graceful rounded arches, the perfect symmetry of the windows in the thick walls, and the soaring vault above.

The abbey at Mozac has some of the most remarkable carved column capitals I’ve seen in any of these Romanesque buildings. There are at least 45 of them, and each tells a stylized story – the Resurrection of Christ, the deliverance of Saint Peter, Jonah swallowed by the whale, and so on.

But there’s another remarkable work of sculpture that caught my eye during this visit: it’s called “The Homage”, and it’s a lintel-piece that’s the only surviving element of the 12th-century section of the cloisters at Mozac. At the center of the relief is one of the Auvergne’s famous “Black Madonnas”, a depiction of the Virgin Mary surrounded by the apostles Peter and John and Saint Austremoine, with a monk bowing in a ritual of homage to the others. (He’s assumed to be the Abbot who was in charge here when the church was built.)

There’s a lot of controversy about why the Madonna is frequently depicted with black skin, but there are 140+ figures like this in France and another famous one just down the street from Mozac in the catherdral of Riom.

Saint Calmin himself is an enduring presence here, too. His relics are preserved in the church’s most valuable treasure, an extraordinary chest commissioned in the 12th century and the largest surviving piece of Limoges engraved porcelain to be found anywhere in the world. The biblical stories and scenes from the life of Saint Calmin are expressed in gold leaf and brilliant colors. It somehow escaped the ravages of the French Revolution, and since a failed attempt to steal it in the early 1900s it is guarded behind a heavy door of iron latticework, but it is an amazing work of art that’s worth a detour to see if ever you are in this corner of the country.

(4) You can imagine the flow of history up to the present day

For me, though, one of the most powerful reasons to visit a place like Mozac is to try to imagine the lives of everyday people congregating here week after week across the sweep of 12 or 13 centuries. No matter what was going on around them – boom or bust, Viking invasions, repeated pandemics of the Plague, wars between local lords and great kingdoms, occupation by Germany in World War II –this would have been the center of a community, a gathering place for neighbors to meet and take stock of their lives.

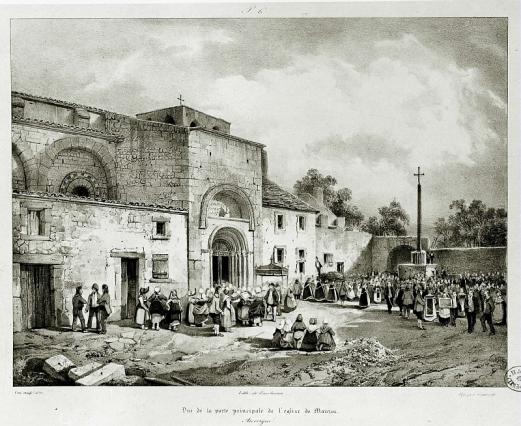

I had that sense particularly on the day I came to Mozac for this visit, a Sunday morning just after mass had finished. There were at least 3 generations of people standing in the brilliant sunlight outside the old church, talking in family groups, the children in scratchy collars and uncomfortable patent-leather shoes, the adults dressed in their Sunday best. I did the math in my head – at least 50 or 60 generations must have passed since the first mass was said here, in every circumstance imaginable.

And I think it’s that – the powerful persistence of community over the ages – that appeals to me as much as the architecture and the history on this incredible site.

Do you have a favorite place from your travels around central France? What exactly appeals to you about it – the art, the history, or something more intangible? Please tell us about your favorite(s) in the comments section below – and please take a second to share this post with someone else who is interested in the people, places, history, and culture of the deep heart of France.

Thank you for this lovely description of this vibrant abbey. Good travels!

Thanks for reading, and for your kind comment!