The main reason to come to Hautefort in the Dordogne region of the deep heart of France is to tour the great Chateau at the top of the hill overlooking the town. It’s an hour-and-a-half southwest of Limoges, and an hour northwest of Brive-la-Gaillarde, but well worth the drive to see this gorgeous example of how a medieval fortress evolved into an elegant country mansion over the centuries. I’ll be doing a detailed report on my visit there in a future post – but for me the trip down the hill to the Musée d’Histoire de la Médicine was in many ways the most interesting part of my day in Hautefort.

The history of medicine

There was a time, in our not-so-distant past, when the practice of medicine was a dark art – a mélange of trial and error, the application of common sense and religious incantation, and medication in the form of mysterious potions and disgusting compounds. When it worked, it seemed miraculous; more frequently, when it did not work, larger forces like the will of God or karma were invoked to explain the failure.

I was reminded of all this history again as I wandered through the Musée d’Histoire de la Médicine. But this museum has another objective, not just to give you the shiver of relief that we live in times when medical care is not such a brutal experience. Rather, it tells a story of how we’ve evolved, too, in the way we think about poverty, disease, and other forces that shaped modern Western culture.

A prison, not a place for medical care

The museum is in the building that housed Hautefort’s 17th-century Hôtel Dieu, “God’s Hotel”. That’s the traditional name for many of France’s old “general hospitals”, evoking their origins as places of Christian care. Today we think of them as medical establishments – but that’s not necessarily how they started.

Of course, there have been places to care for the sick for many centuries, and the name “Hôtel Dieu” goes back much further than the 17th century. In France, more specifically, to be called a “Hôtel Dieu”, a place had to be under the control of a Bishop and near a town’s central cathedral, and its principal mission was to “care for” poor people in its jurisdiction.

But “care for poor people” was not necessarily a medical mission by the 17th century when the Marquis of Hautefort founded this place in 1669. Rather, as the museum’s exhibits point out, this Hôtel Dieu was originally more a kind of debtor’s prison.

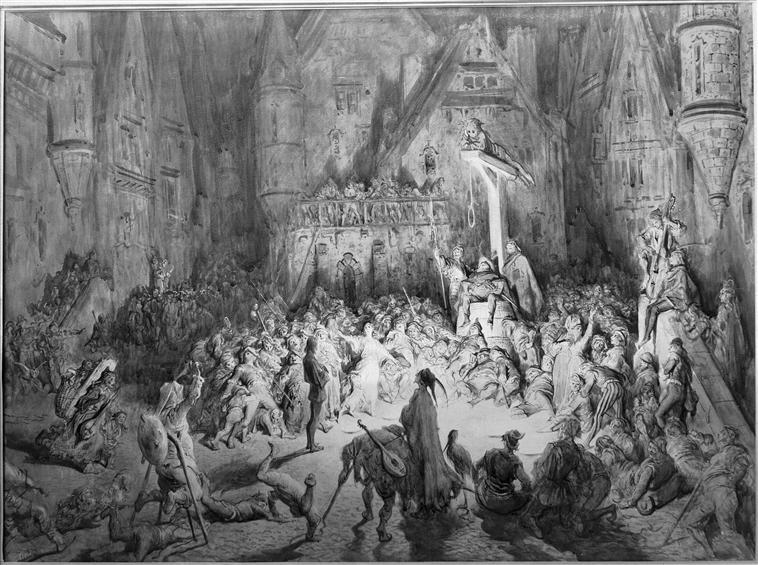

Poverty swept across the French countryside in the late 1500s and early 1600s. Slums were called ironically “cours des miracles” (“courts of miracles”) and spoken of in the way some people talk about mythical “no-go zones” in Paris and London – concentrations of poor and homeless people living in the most miserable conditions imaginable. Places like this were established by order of the King “to avoid begging and idleness…to confine beggars” and put them to work; they were built “only to confine and imprison, without any healthcare motivation.”

A sad and remarkable “tower”

One striking expression of the Hôtel Dieu’s vocation to “care for poor people” is present in the very first room of the Medical History Museum at Hautefort. It’s a little wooden “tower”, essentially a cupboard with a revolving door. It’s purpose? To make it possible for poor parents to abandon their children into the care of the religious order under the cover of anonymity.

Between 1790 and 1847 (when the practice was stopped), the revolving door at Hautefort was used 1,947 times (!) to pass a child from the street into the Hôtel Dieu. In each case, parents were supposed to affix a little cloth ribbon to the infant’s clothes so that, if they had second thoughts within the first 24 hours after the abandonment, they could identify and reclaim their child. These colored strips were dutifully attached to the baby’s entry in the town’s records, although there’s no evidence of how many of them were ever reunited with their families.

An evolving medical mission at Hautefort

Of course, the meaning of “care for the poor” evolved over time, and by the 18th century the institution began to function more and more like a real “hospital”, in the modern sense of the term.

The religious vocation of the Hôtel Dieu evolved, too, and it is evident everywhere in this building at Hautefort, from the massive stone cross out front to the fine little chapel containing a mausoleum in which the Countess of Hautefort and the Baron of Dumas are entombed.

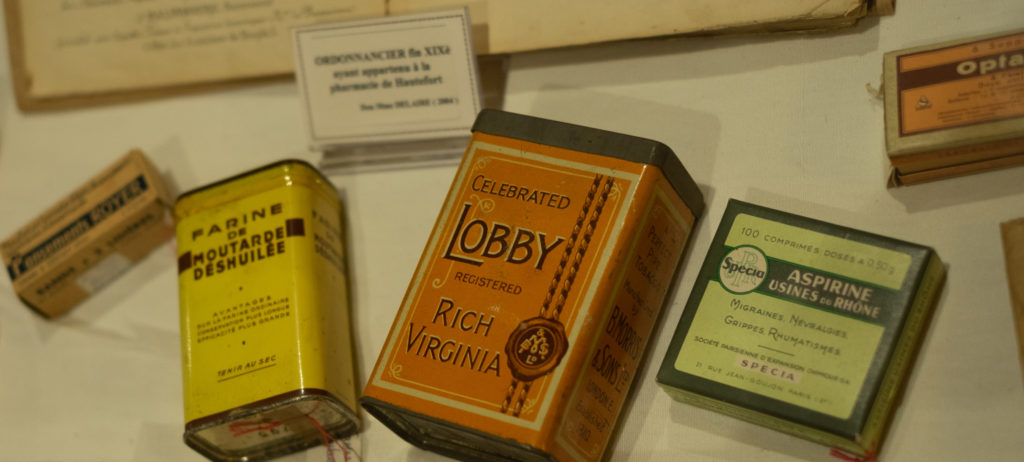

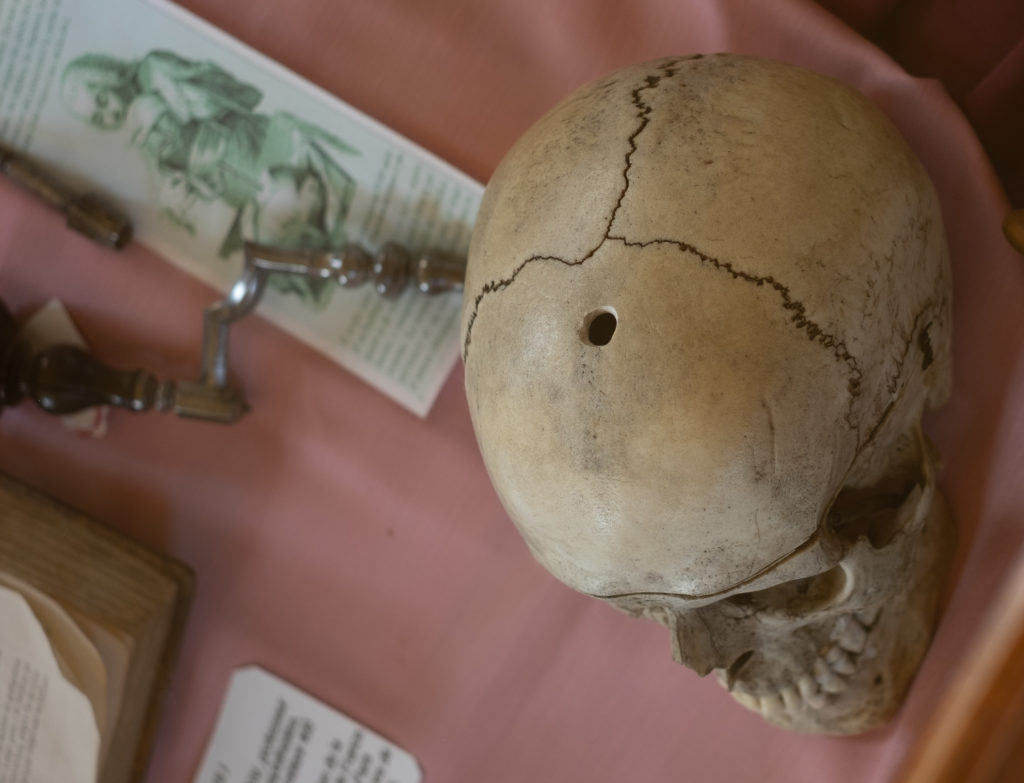

But the most remarkable aspect of this Medical History Museum is the story it tells about so many different branches of medicine and how they have changed over time – whether it’s about dentistry, gynecology, radiation, prosthetics, pharmacy or surgery. Here are a couple of the exhibits I found most interesting along the way:

- The history of treating the Black Plague. The first thing you notice is the striking costume worn by the “Pest Doctor” – a uniform straight from a horror film, and surely something that would make a patient feel worse as she saw the doctor approaching! But despite its look, the costume was meant to keep the caretaker from contracting the terrible disease through contact with the skin of the patient or breathing the “foul air” of the sick room.

- The evolution of the dentist’s office. I have a deep-seated fear of dentists – they couldn’t scare me more if they wore the “Pest Doctor’s” uniform! – so I was especially fascinated by the museum’s collection of dental tools, many of which were apparently to be applied with brute force and without the benefits of anesthesia. But it was interesting, too, to see how the basic outline of the dentist’s workspace has remained the same over the last 200 years, even as the tools evolved and became more “humane” in the process.

- The explosive expansion of surgical knowledge. This exhibit features another costume – this time, the outfit worn by an 18th-century surgeon in France. It’s a reminder of how the profession became a distinguished, almost noble occupation when King Louis XV created the Royal Academy of Surgery in 1731. This society was a real expression of the Enlightenment in France, a time when value was given to shared experimentation and intellectual exchange as a way to advance the medical arts more rapidly. The French Royal Academy, as the museum’s signs note, quickly spread its concepts and expertise through the whole of western Europe.

- A sad reminder of the importance of war in the advancement of medicine. Perhaps the most moving (and troubling) exhibit, for me, was a little section of the museum dedicated to prostheses created for soldiers returning from the horrific battles of World War I in northeastern France. We’re often reminded of the millions who died immediately in those battles, but less frequently of all the men who had to come home missing arms, legs, hands, and eyes. Every piece on display in this exhibit was a reminder how hard it must have been for each of these soldiers to adjust to a new life, a new way of functioning in just the most basic ways after the war.

A day in Hautefort worth remembering

So, yes, the Museum of Medical History can be a little distressing at times, and many of the exhibits can leave you feeling a little melancholy. Still, it’s a remarkable story of the progress we’ve made over the centuries, and a remarkable study of the ingenuity of ancient doctors who had to treat patients without all the advantages we enjoy now.

That great chateau up the hill is also a good reason to visit, of course. So if you find yourself on holiday or living in the Dordogne, please consider making the trip to Hautefort – it’s a visit you won’t regret!

Other places in France have museums about medical history – have you seen one of them? What made the biggest impression for you? What other museums like this can you recommend? Please share your experience in the comments section below. And please take a second to share this post with someone else who may be interested in the people, places, and history of central France!