A battlefield on top of a mountain

Old battlefields are sometimes hard to decipher. As the years pass, even deep shell craters lose their sharp definition, bullet marks on stone walls are worn down, and the whole landscape takes on a settled, green calm that belies the violence that once marked the place. A great effort of imagination is required to reconstruct troop movements and the profound drama of long-ago conflicts.

That’s especially the case today as I finally arrive at the top of the hill at Mont Mouchet. In early June 1944, at the same time all hell was unleashed on the beaches of Normandy far to then north, another battle was unfolding in this unlikely corner of the deep heart of France.

We’re in the département of the Haute Loire, near the headwaters of that great river, in the massif of Margeride (part of the mountain ranges that make up France’s massif central). The summit is 1,497 meters (4,911 feet) high, and from here you can see “a splendid panoramic view over much of Central France from the Massif Central to the Alps”, as Wikipedia puts it.

That’s a primary reason Mont Mouchet was chosen as the assembly point for a major gathering of French Resistance fighters in 1944 – it would be easy for Allied pilots to find in the landscape when they came to drop supplies and ammunition. It’s also far from almost everything else in this remote region; I should have been tipped off by the Michelin Guide’s note when I left the main road in Langeac – “31 miles, allow 3 hours” to go there.

"The largest assembly ever of French Resistance fighters"

Isolation was part of the plan in 1944, though. In the beginning, the area around Mont Mouchet became known among as a good hiding place for people trying to escape forced labor in Germany (the dreaded Service de Travail Obligatoire, or S.T.O.). Hundreds – perhaps thousands – had already taken refuge in these mountains. Some number of these refugees gravitated naturally to “taking the maquis”, joining up in the clandestine units of the French Resistance and participating in small acts of sabotage whenever the opportunity presented itself. These units eventually took on a more formal organization and came under the umbrella of the “secret army” called the F.F.I. (Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur).

As plans for the great D-Day invasion began to take shape at Allied HQ in England, someone decided it would be useful to have some kind of concerted action in the center of France to put up as many barriers as possible to the German armies in the south of the country, keeping them from moving north to reinforce their presence in Normandy.

The request was passed to the head of the F.F.I. in Auvergne, “Colonel Gaspard” (real name: Emile Coulaudon) during a meeting in Montluçon in April 1944. By mid-May, several different clusters of maquis were being made ready to fight in the coming battle, including 2,700 men at the hideout of Mont Mouchet. At Clavières, one of the entry points to the mountain, they put up a sign saying “Ici, commence la France libre!” (“Here begins Free France!”) Arrangements were made to parachute large quantities of arms and ammunition onto the top of the peak.

And then the Germans came to Mont Mouchet

And then the Germans came, intent on “re-establishing the authority of Occupation troops in the Cantal, combatting and destroying the Resistance groups by all means available”, according to their General Jesser. The first Nazi battalions attacked 3 nearby villages on June 3rd, three days before the D-Day landings at Normandy; it appears they suffered heavy casualties, while the maquis defenders reported only a few.

More skirmishes followed, each apparently more intense than the one before. The different histories I’ve read describe the Germans as “relentless” in their pursuit of the maquis, and by June 10th they had been reinforced with 3 columns, a total of 2,800 to 3,000 German soldiers equipped with machine guns mounted on trailers, light mortars, and anti-aircraft cannon. Fighting on that day was inconclusive, but violent; the men of the French Resistance managed to keep the Nazis at bay throughout that day, destroying several vehicles, capturing a couple of cannons, and taking some German prisoners.

They knew, though, that the attacks would come again the next day, and on June 11th the Germans unleashed a barrage of artillery and air raids on the maquis still grouped around the Maison forestière, their headquarters at the top of Mont Mouchet. Attacks were renewed in the surrounding villages, too, and the Resistance troops began to run out of ammunition. Some of the maquis companies reportedly lost as many as a third of their men in the fighting.

Plans were made to withdraw and regroup. By the time the Germans arrived at Colonel Gaspard’s house on top of the mountain, the Resistance army had vanished into the night. Some of these units would regroup again in the following weeks and continued to harass the enemy, doing everything possible to slow down or stop their advance.

It’s hard to know with any certainty the real effect of their determined resistance, harder still to know exactly how many French fighters were killed or wounded in their attempt to block the German advance; I’ve seen estimates ranging from 119 to 260 dead, 60 to 150 injured, against roughly the same numbers for the Germans.

We do know that the Nazis followed their brutal practice of taking hostages and killing them in reprisal for their support of the Resistance in the villages around Mont Mouchet. In the aftermath of the battles of June 10th and 11th, the Germans pillaged and torched the villages of Clavières, Lorcières, Paulhac, and Ruynes-en-Margeride, as well as most of the farms within a 10-km radius around the mountain. Around 60 locals were rounded up and shot dead in the process, and another 120 were deported to German concentration camps in the east.

The remains of Colonel Gaspard’s Maison forestière are still here, grown over with wildflowers in the crisp high-altitude air, but there are no other visible signs of the maquis encampment here. Instead, the place has been given over to remembering “the place where (along with the one at Vercors) were gathered the greatest number of Resistants ever at one time in the national territory of France.”

A Day Trip to Mont Mouchet

When you go to Mont Mouchet today, though, you’ll find it hard to reconstruct all this activity, although the long approach on narrow, tightly-wound “D”-roads will certainly give you a sense of why this was considered a great place to assemble far from the eyes of the German occupiers. This is beautiful, mountainous farmland, very sparsely inhabited, a green and remote corner of the deep heart of France.

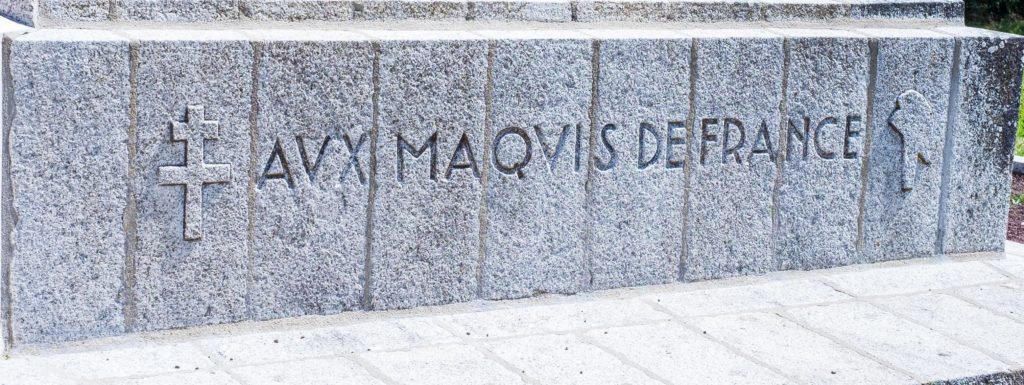

“Colonel Gaspard” (Emile Coulaudon ) himself was here when the first stone to a memorial – a “National Monument” -- to these fighters was laid in 1945. The site was formally dedicated on June 9, 1946 in a solemn ceremony featuring many of the men who had fought here. The sculpture is the work of Raymond Coulon, a Parisian artist, and it depicts two well-armed maquis fighters alongside a column with the insignia of many of the units that made up the F.F.I. and other branches of the French Resistance. An “eternal flame” burns next to the sculpture, dedicated to the memory of an Unknown Maquis.

There’s a fine small museum here, too, documenting the whole history of the Resistance in central France. I especially appreciated the way the exhibits are tied together by the story of two local men, “Lucien” and “Pierrot.” Their growing anxiety about the war in 1939 gives way progressively to an active engagement in the Resistance and ultimately in the fighting that took place around this mountain. It’s all told in comic-book form, with panels alongside each of the museum’s main exhibits of documents and memorabilia related to the maquis of this region. (And you can pick up a copy of the full comic-book version in the gift shop at the end of the tour.)

Fifteen years after the battles, President Charles De Gaulle came to Mont Mouchet for the annual ceremony of remembrance. On June 5, 1959, he told the assembled crowd, “What happened here is an episode that is too-little known, but heroic in the history of the French Resistance.” Successive Presidents of France have come here regularly to reinforce that message.

Even if it is hard to see the actual events in the mind’s eye in the midst of this quiet, beautiful region, the trip I made here helped me understand just how much this corner of France contributed to the eventual liberation of the country.

What sites have particularly moved you in your travels around France? Have you seen other evidence of the effects of the French maquisards on the outcome of World War II? Please share your experience in the comments section below. And while you’re here, please take a second to share this post with others using the button(s) below for your preferred social-media platform(s). Thanks!

Fascinating…it’s a period of history that captures my imagination as I wonder what I would have done, and how I would have reacted. Thank you.

Any mention at the memorial of NANCY WAKE of one of the leaders of the French resistance at Mont Mouchet and elsewhere throughout France. Also known as “The White Mouse” by the Gestapo and number one on their most wanted list. Nancy was the Allies most decorated servicewoman of WWll.

Thanks, Kurt, I had not heard of her — and I missed any reference there might be in the little museum at Montmuchet. Your comment provoked me to do some research, though, and she is incredibly fascinating! I will certainly look for information about Nancy Wake in my next visit to this area and try to tell her story in a future post. Thanks for letting me know her importance!

There is a fabulous book written about her, “Code Name Hélène”, by Ariel Lawhon, I highly recommend if!

Thanks for the recommendation – I’ll look for it!

Hi, Kurt ,Nice to read your words. Thank you to let me this great woman, a flighter in WW2

For more in famous and hardly known heroic women who fought for liberty in France from the Nazis read “A Woman Of No Importance.” The story of Virginia Hall, a SOE/OSS operator who organized the resistance in France throughout WW2.

I’ve just finished reading it. Amazing story. Amazing woman. Many of the male so-called ‘leaders’ of the Maquis do not fare so well in this extremely weel researched and well written book.

They fared amazingly well. Given the macho man culture of the Maquis, they just had to accept that she was the boss ( chef du parachutage), because without her they would not have received air drops from Britain. Without her they would not have retreated from Mont Muchet so successfully and regrouped at St. Santin because Fournier’s men had meticulously planned the retreat to avoid The Germans. Nancy Wake instilled in The Maquis Plan A: to attack and always a compulsory Plan B: retreat to a rendezvous point. Of all the books written I still prefer Nancy Wake by Russell Braddon (1956).