A castle distinguished by its power

There are thousands of castles in France. Most of them are very small, built to be the medieval homes of some minor aristocrats or to protect travelers along a stretch of road. (We’ve covered many of these smaller places on this blog – the fine chateau at Tournemire, for example, or the family castles at Val, Domeyrat, Arlempdes, and Billy.)

At the high end of the range, you know some of the others already – the great, graceful palaces like Chambord and Chenonceau in the Loire Valley that retained some of their defensive structures but that obviously focused more on the royal luxury of the kings and queens who lived there.

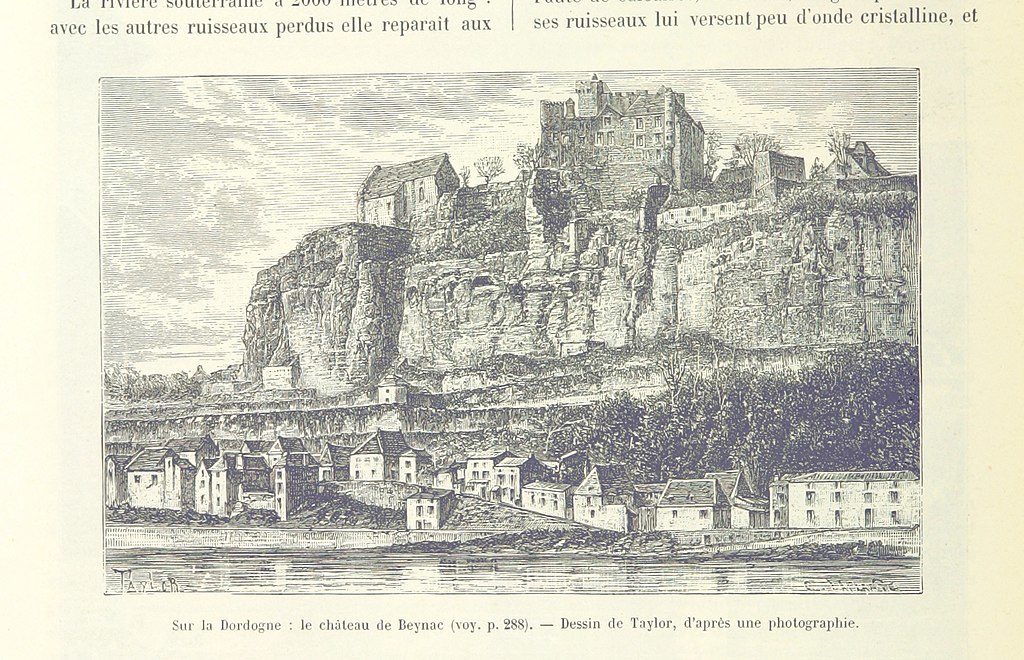

There’s another category of castle, though: the ones that clearly meant business, fortresses created mainly for serious military action, small towns hardened for war. One of these mighty fortresses dominates the rocky bluff over Beynac in the Dordogne. As a bonus? The village surrounding it is also on the official list of “Most Beautiful Villages in France.” (Its official name is Beynac-et-Cazenac because the village merged with the commune of Cazenac in 1827 – but, really, Beynac is the main attraction and even the town’s official website refers to it simply as “Beynac”.)

Coming into town

You’ll know as soon as you see it on the horizon that he chateau at Beynac must be a big deal – it’s even featured in one of the travel videos produced by Rick Steves. It’s an incredibly popular tourist site. The village is layered up and down the side of the hill, beginning along a narrow 2-lane road at the level of the Dordogne River. You’re only 10km (6 miles) away from Sarlat, and it’s an easy 15-minute drive from here to several other remarkable sites clustered in the same valley.

Even after the August crowds had left, when I came to town the traffic was chaotic. Two camping cars met on the narrow street and everything else slowed down as they painstakingly navigated to avoid scraping against one another. I had to pass through the parking lot by the river several times before I finally found a space. And it was amusing to watch the waiters at one of the riverside restaurants as they balanced trays of food and bottles of wine, maneuvering deftly between cars as they carried orders out to people eating on the terrace across the street.

When you come to Beynac, be prepared for a serious hike up to the castle at the top of the bluff. These are narrow cobblestone streets, and in many places the stone steps are worn down and it’s difficult to find your footing. And the climb is steep! Fortunately, there are a couple of small restaurants on the way up if you need to stop to catch your breath and have a coffee.

In the footsteps of Richard the Lionheart and Simon de Montfort

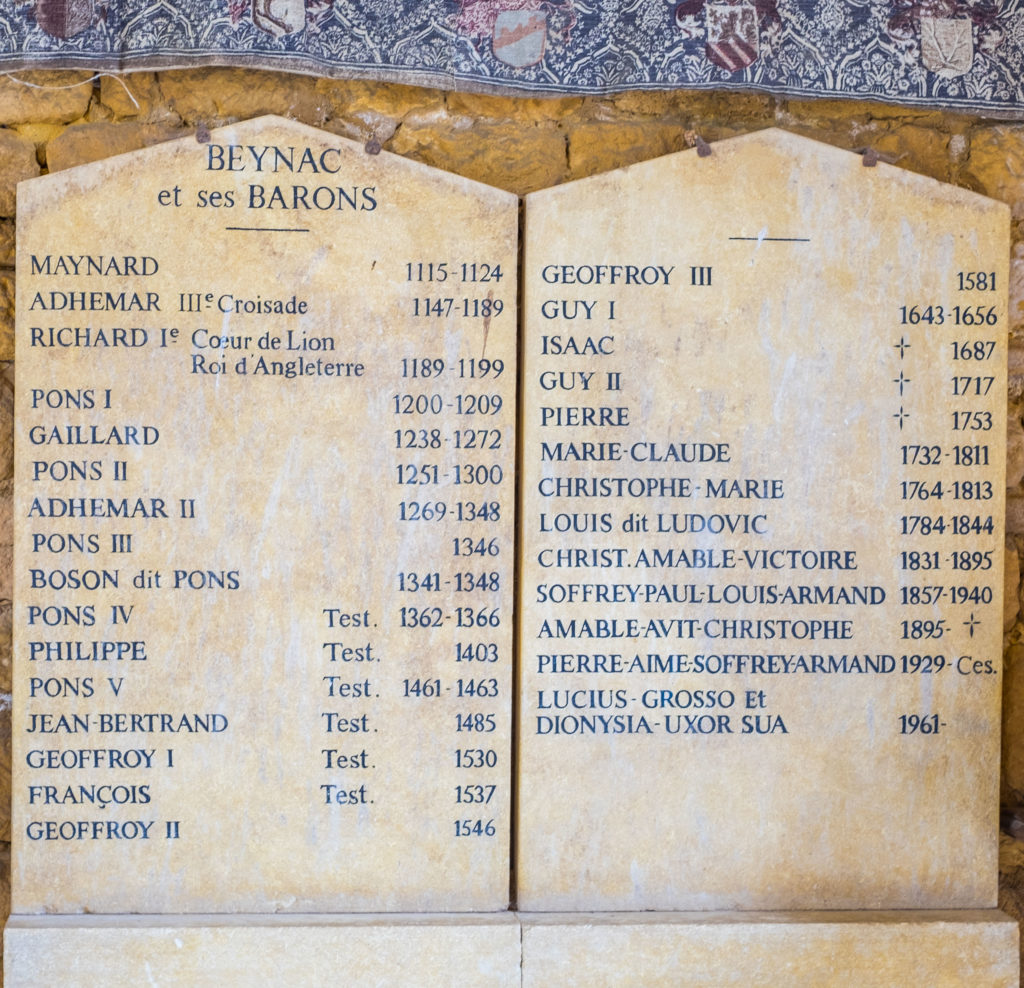

The first known Baron of Beynac built a castrum here around 1050 A.D.; the first part of the existing chateau (built in the 1100s) was the keep, the great tower rising in the middle of the site. From this height, the first lords of Beynac could see up and down the Dordogne and the roads crossing it for miles; that visibility alone was a source of power for these first barons, since it gave them the ability to sell protection, tax commerce, and protect their properties.

Then the wars came, and they came in waves. This was a very powerful and notable family, so it’s not terribly surprising that Adhemar, the second Baron of Beynac, was tapped to go off to the Holy Lands during the Second Crusade. When he died, though, he left no heir – and Richard the Lionheart saw an opening. He put the castle in the hands of one of his trusted friends and held it in the name of the King of England from 1189 to 1199.

The Beynacs didn’t give up, though. Richard the Lionheart died from a crossbow accident in 1199, and Pons (the brother of Adhemar) waited a few months before he had Richard’s friend assassinated in the street at Bordeaux. Pons reigned as the third Baron of the castle until 1209, loyal to the Count of Toulouse.

If you look at the list of the chateau’s owners, though, you’ll quickly notice some odd gaps and overlaps, many of which reflect the constant chaos swirling around ownership of the site. In 1209, the Pope launched his infamous Albigensian Crusade, ostensibly to root out the heretical Cathars who inhabited southern France. As a bonus, though, it provided a convenient path to get rid of the Count of Toulouse, who (although he himself was Catholic) got himself excommunicated for defending the Cathars. All this turmoil brought the notorious Simon de Montfort, leader of the Crusade army, to Beynac in 1214; you won’t find his name on the list of the legitimate Barons of the chateau!

Then, the long war between France and England

Americans and their European friends agonize as the war in Afghanistan drags on for 17 years. Try to imagine, then, the physical damage and psychological stress that must have dominated the lives of people in this part of France as armies of the English and French kings fought each other for 116 years. (It’s called the “Hundred Years War” but in fact it lasted from 1337 to 1453.)

As it was in World War I, as it is today in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, the opposing armies clashed violently just to gain a small scrap of land, a particular chateau or village, only to lose it again to the other side, then take it back again. Beynac itself flipped back and forth as the two armies repeatedly laid siege against the town.

This was war in the bloody tradition of Montagues and Capulets, or Hatfields and McCoys. Here, though, it was on a much larger scale, the House of the Plantagenets (the English) against the House of Valois (the French). It’s the war that rings in the ears of students of European history, replete with familiar names like the Black Prince, Joan of Arc, and the battle at Agincourt.

Historian Maurice Keen described the war this way for the BBC:

“[England’s objective was to] render substantial regions of France virtually ungovernable from Paris, and to keep the fighting on French soil going in between occasional English expeditions. The conquest of territory was not an object. {…] Though intermittent, these expeditions had a very major impact. They took the form of large-scale, swift-moving military raids (chevauchées) deep into France and were intended, through systematic plundering and the burning of crops and buildings, to damage the economy and undermine French civilian morale.”

Rick Steves says it more succinctly in his video about the castle. Standing in a doorway overlooking the courtyard at Beynac, he says, the lord of the manor would announce to his people

“Now you are French,” or “Now you are English – in any case, deal with it!”

(If you want an idea about how ugly and traumatic this war might have been, be sure to drive across the valley from Beynac to visit another of France’s “most beautiful villages” at Castelnaud-la-Chapelle. These two massive blocks of military might regularly faced off against each other during this period; Castelnaud has an extraordinary “Museum of Medieval Warfare” within its walls, complete with every variety of gun, sword, crossbow, and siege engine you can imagine. I highly recommend a visit!)

Visiting Beynac today

I could go on about the other conflicts that came to Beynac over the centuries – the Wars of Religion, for example, or the indignities it suffered during the French Revolution. What’s remarkable, though, is that through all this turmoil the place remained more or less in the hands of the same family until 1962! It grew, of course, over time – you can visit the Great Hall where the Barons convened their councils, the little painted chapel, and the Renaissance-era buildings that show how the castle evolved into an aristocratic residence.

This is truly an area where you could spend several days. A hotel or apartment in Sarlat makes a fine base for visiting the “most beautiful villages” clustered along the Dordogne at La Roque Gageac, Domme, Castelnaud-la-Chapelle, and of course here at Beynac. The beautiful, abstract Gardens at Marqueyssac are a good place to start, since you can see all the other sites from the belvedere at the end of the gardens.

How to Get There / Practical Information

Beynac-et-Cazenac is located on route D-703

- 10 minutes from Sarlat-le-Caneda

Nearby railway stations

Sarlat

The Chateau de Beynac is open 7 days a week year round

(except January 8 - February 11)

Official Website (in English):

Have you spent time at Beynac, or any of the other great military castles in France? What interested you most? Please share your experience in the comments section below. Take a second, too, to share this post with someone else who’s interested in French history and travel ideas.

Oh wow! I am adding this to my research of places to visit on my next trip 🙂 Your site is amazing, thank you for searching so much historical info and photos!

Thanks for reading – happy travels!