A country built by migrants

As the debate over immigration rages across the front pages of newspapers and in the nightly TV talk shows across France, it’s easy to forget that modern France – our concept of Paris and the country it represents – is itself less than 250 years old. It’s easy to forget, too, that what we think of as “France” today was built in large part by massive waves of internal migration. And one of the largest of all these “immigrant” populations…came to Paris from the Auvergne, in the Deep Heart of France!

Of course, people had found their way from the Auvergne to Paris in small numbers for centuries, and some of them (Blaise Pascal, Sidoine Apollinaire, Lafayette, Napoleon’s General Desaix, and the Michelin brothers, to name just a few) left a grand mark on the country’s history. But for a very long time, most people looking to migrate away from central France looked further south, rather than to Paris. Graham Robb, in his extraordinary book The Discovery of France, describes the situation:

“The capital was well served by the major rivers of north-eastern France – Yonne, Seine, Marne, Aisne and Oise – but not by the rivers that rise in the Massif Central. The best roads out of the Auvergne all led south. A trade route to Bordeaux, Toulouse, Montpelier or Marseille, busy with mule trains and pilgrims, was preferable to an obscure track that led north into lands where people spoke a different language. Even in the early twentieth century, many villages in the southern Auvergne and Périgord had closer ties with Spain than with the northern half of France.”

[And an editorial note: If you’re interested in the history of France and you have not yet read Robb’s book – please do! The Discovery of France is one of the best and most interesting stories of how modern France emerged from the chaos of small local fiefdoms and tribal customs, and I recommend it more than almost anything else I’ve read!]

It was only in the mid-1800s, taking advantage of the new system of national railroad lines, roads, and canals pushed by Napoleon, that commercial traffic and the flow of immigrants got re-oriented more to the north, to Paris. As the Industrial Revolution swept through France, great agricultural regions like the Auvergne and the Aveyron began to suffer, and larger numbers of people began to look somewhere further from home to escape their poverty.

Looking for work in Paris

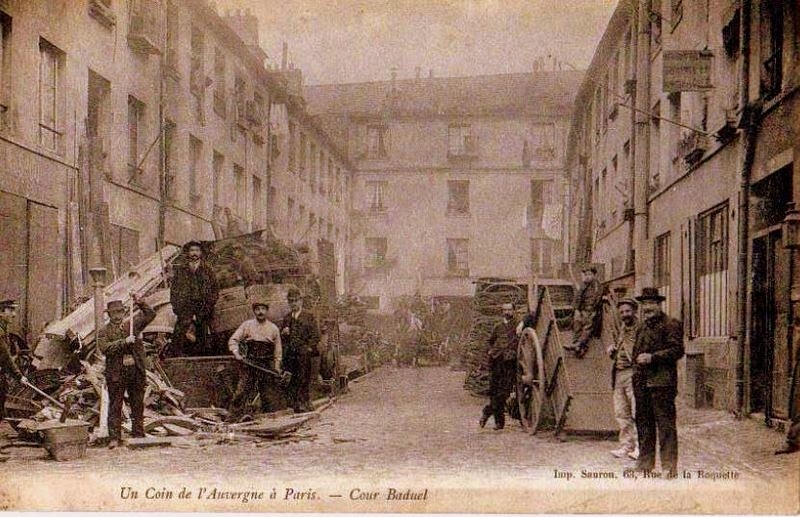

In the beginning, particularly, Auvergnats would take on just about any work they could find in Paris, although Robb points out that they brought many of their homegrown specialties with them to the big city: “The Auvergne sent hatters and sawyers from the Forez, rag-and-bone men from Ambert and Le Mont-Dore, and furriers from Saint-Oradoux who walked the streets under a mountain of rabbit skins, frightening children and skinning stray cats,” he says.

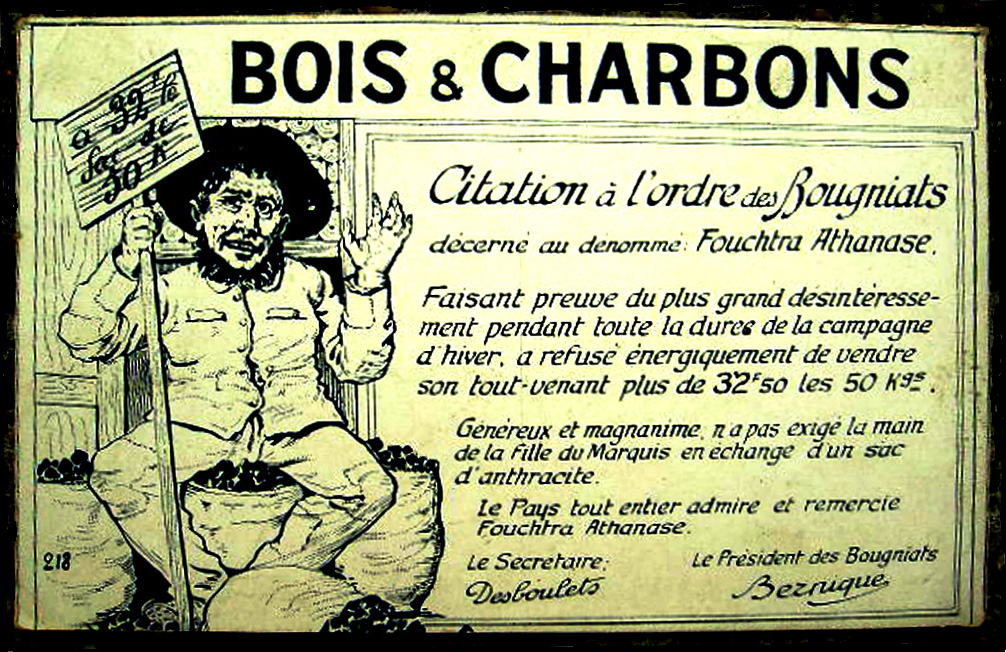

Over time, though, these migrants from the country’s center seemed to settle on a direction, a “chosen domain” for their work: selling wine and coal. It’s a reminder that the Massif Central in mid-1800s was a major center of coal production in France; we know, for example, that the flow of coal to Paris coming up the canals from Brassac-les-Mines was an early important influence in bringing Auvergnats to Paris.

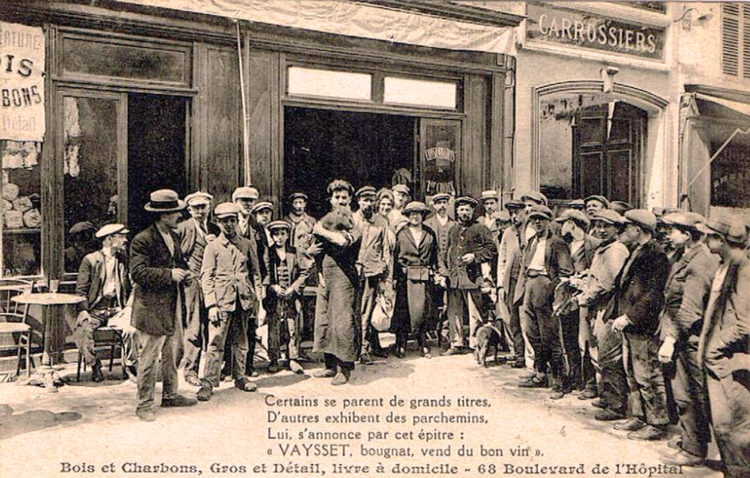

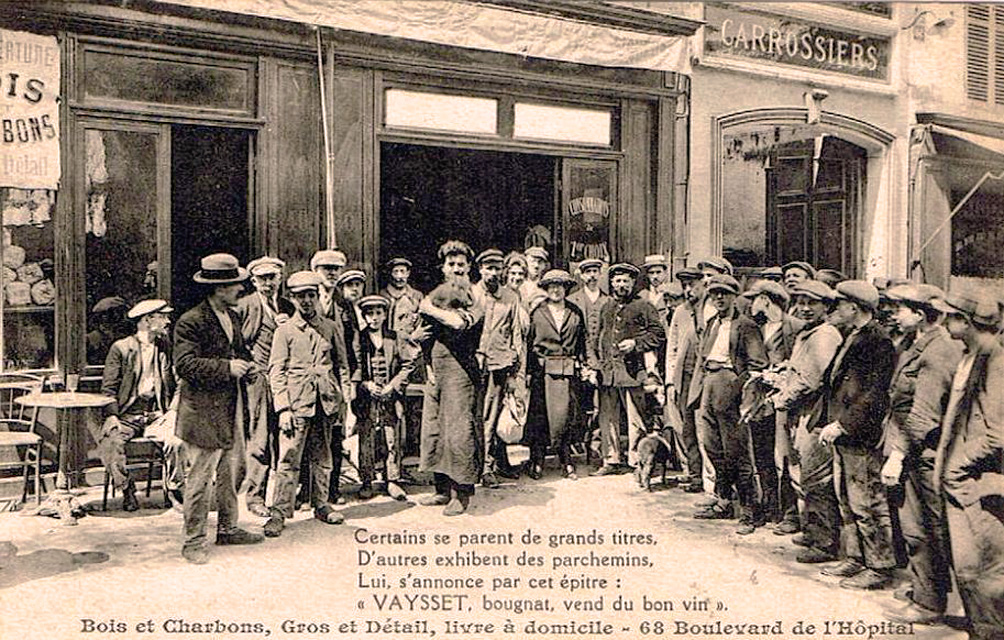

As their numbers increased, they even got a specific nickname: charbougnats, then just bougnats. It’s a contraction in French of “marchands de charbon” (coal sellers) and “Auvergnat”, and it’s still a familiar word today. Widely stereotyped for their country-bumpkin manners, they were also recognized as incredibly hard workers with skills that didn’t really exist commonly in Paris.

... and on to the restaurant business!

As years went by, the profession of the bougnats evolved again, and many members of the migrant community went into the restaurant business. And here you can find some of their most remarkable legacy, visible everywhere in the city today.

Graham Robb describes their influence: “The Auvergnat coal merchants called bougnats sailed down the Allier and the Canal de Briare. Most of them also sold wine. Some of the best-known cafés in Paris were founded by the bougnats – Le Flore, Le Dome, La Coupole, Les Deux Magots. There are still a few coal-selling barkeepers, and almost three-quarters of the cafés-tabacs in Paris are still run by Auvergnats and their descendants.”

[There’s a fine website called L'Auvergne Vue par Papou Poustache where you can see many more interesting historical photos of bougnats and their communities in Paris.]

A talent for organization

Another part of the bougnat legacy is especially striking to me. The people who came out of the deep heart of France to settle in Paris really have a talent for organizing themselves. From the 1800s on, they started clubs called amicales and published their own newspapers; you can still find a Ligue Auvergnat (“Leaugue of Auvergnats”) with an extremely robust website and program of activities (including a huge Christmas party on December 16th), and there’s a whole federation of Amicales de Cantal, too. A newspaper called L’Auvergnat de Paris is now 131 years old, still publishing new content every week “devoted to the café, hotel, and restaurant businesses”.

Music from the Deep Heart of France

And they were never only about business. The bougnats brought the culture of their homes in the Auvergne and the Aveyron to Paris, too. The most notable example of this, still around today, is the music associated with the bourrée and the big dance events called bals-musette. The music is distinctly Celtic sounding; some of the bourrées I’ve heard sound almost like they might have come from a recording by the Chieftains, with lots of bagpipe and hurdy-gurdy in the mix. Here’s a charming video of the style from the early 1900s:

… and here’s a more modern example by Le Beau Milo released earlier this year:

(If you’re interested in modern jazz, it’s cool to know, too, that the bourrée was an important influence on the way this music evolved in France. I’m a huge fan of Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grapelli, so it was fascinating for me to learn that they started playing in clubs that organized bals musette when they first came to Paris in the early 1900s. This is music that is profoundly Auvergnat – that’s why it’s featured so prominently in the remarkable MuPop Museum of Popular Music in Montlucon. If you’re interested, it’s well worth a day trip from Paris!)

Lunch with the legacy of the bougnats

So the migrants who came to Paris from the deep heart of France have had a lasting impact on this most visible of all French cities. Karen and I experienced a little of the bougnat culture for ourselves in September when we went for lunch at the Ambassade d’Auvergne (the Embassy of Auvergne) at 22, rue du Grenier Saint-Lazare, near the Pompidou Center in the 3rd arrondissement.

Open since 1966, it has a rustic interior reminiscent of some of our favorite auberges in the center of the country. And the food… the food is pure Auvergnat, from the showy presentation of aligot (a gooey mash of cheese and potatoes, one of the real “comfort foods” of France) to the quality pork and beef sourced from the Auvergne.

A profound influence still in force today

It was a classic experience in cuisine from the deep heart of the country, and proof once again of the persistent influence of the bougnats and their descendants in Paris. It’s estimated that 500,000 people living in the capital city today can trace their roots to the Auvergne and the Aveyron and the great waves of migration that started there more than 200 years ago.

The national TV chain, TF1, reported on their influence in 2015. “Paris wouldn’t have the same face without the Bougnats!”, the reporter claimed. “It’s the liveliest and most structured community in the capital.” All the evidence I’ve seen shows that it’s still the case today!

What about you – have you encountered traces of the bougnat culture in your visits to Paris? Have you seen signs of other regional or provincial immigrants from other parts of France in the capital? Please tell us about your experience in the comments section below. And, as always, I’d be grateful if you’d take a second to share this post with someone else by clicking on the button(s) to pass this on through Facebook, Twitter, or your other preferred social-media platform!