Cet article est consacré à mon ami Luc-Emmanuel (qui m’a convaincu de reprendre ce travail en tant que blogeur et qui m’a posé la question à la base de cette réflexion) et à Karen (ma chere epouse qui tolere mes marottes et qui est ma partenaire dans cette aventure.)

Is there someplace in the world (other than your actual home) that feels like home to you? Someplace that is instantly comfortable – a relative’s house, a specific beach, some small town or a sprawling city -- where you can imagine spending significant chunks of the time remaining to you on this planet?

Since I started this blog six years ago, people have regularly asked me “What is it about France that draws you in so deeply?” To be honest, my wife often asks me that, and she lived there with me for seven years! Even people who know France well themselves sometimes have a follow-on question: “I get why you might want to live in Paris or Lyon, but really, the Auvergne? The ‘deep heart’ of the country? There’s nothing there but factories and cows!”

I’ve come back to these questions repeatedly over the last few months as I have struggled to find the motivation to add new stories to this site. 2022 was the first out of the last 24 years when I did not spend at least part of the year exploring the back roads and the historical depths of central France, and I have missed it more than I ever thought I would. We’ll be going back for an extended visit this summer (touches du bois!) but it’s time for me to reconsider my motives for writing about France and reconnect with why it is so important to me.

In the Aubrac: “They have more cows than people”

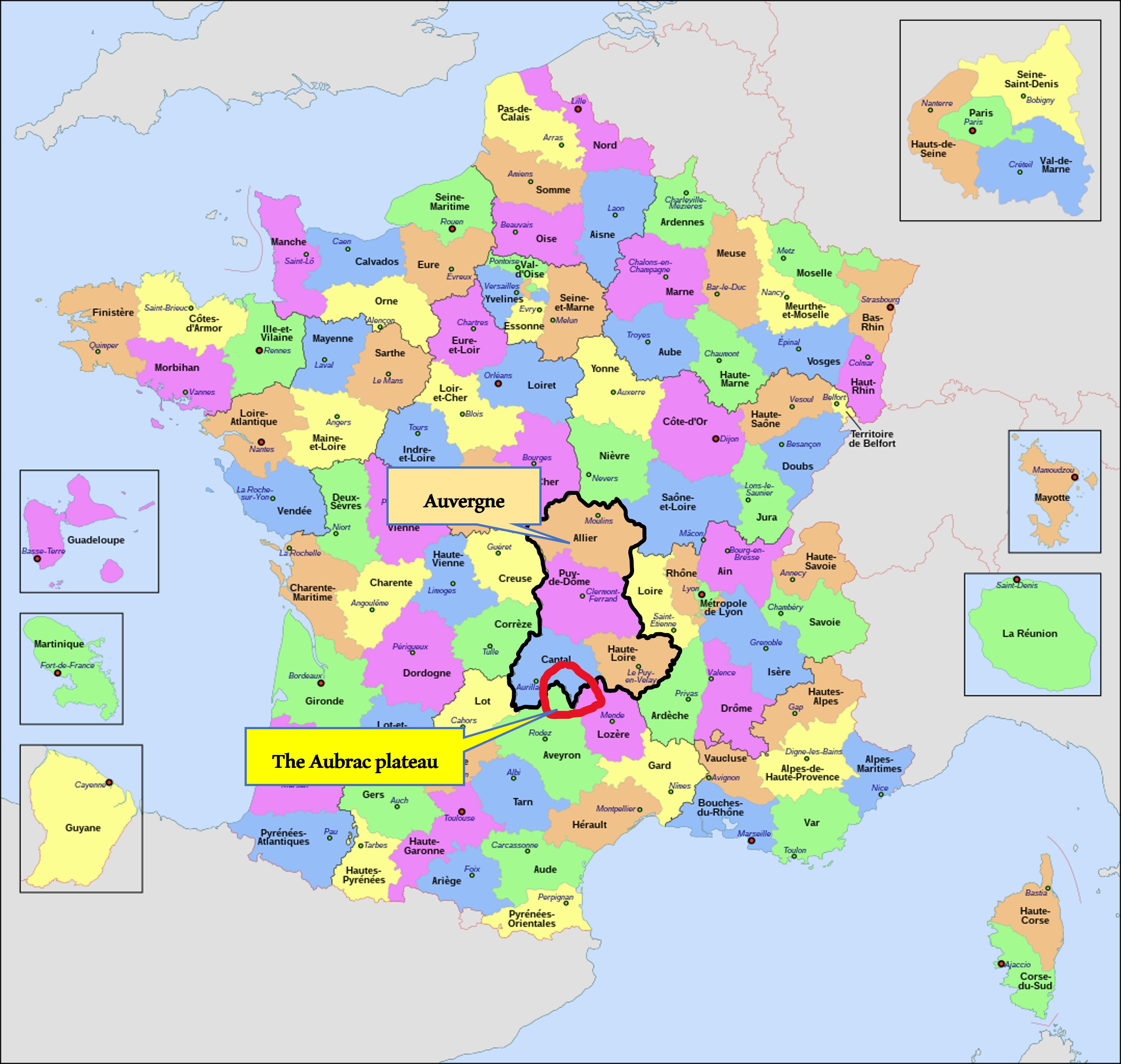

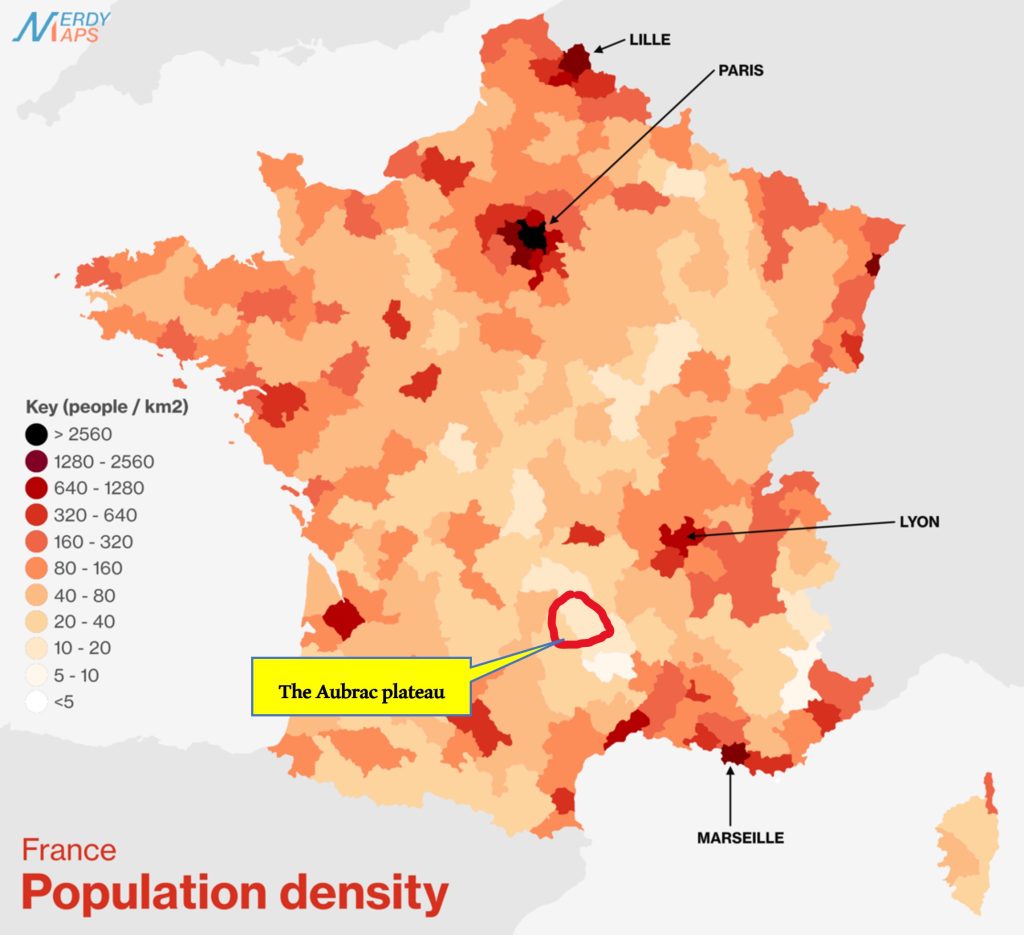

This whole reflection started when I spent a long afternoon combing through the photos I took during my last visit in the Aubrac, that wild and beautiful part of the Auvergne which is among the most sparsely populated regions of France. It’s not even well known to most French people, so it’s certainly not a place often seen by tourists.

Technically, the region is a plateau spread out over an ancient lava flow. (“Aubrac” comes from “Alto Braco” – “High Place” – in the old language of Occitan.) And though I personally associate it most with the southern part of the Auvergne, the Aubrac is actually a very large region – 1,500 square kilometers or 580 square miles – touching three different départements – the Cantal, Aveyron, and Lozère.) Much of its territory is formally reserved as a regional Parc Naturel. Its grandest “city” (1,200 people) is Laguiole, famous everywhere in the world for its distinctive high-end knives. (Laguiole’s history is itself a remarkable story of coming back from the brink of total obscurity; I’ll do a separate post on my visit there in coming months.)

The manufacture of knives is important, but the main industry here, for obvious reasons, is bovine breeding. If people from other parts of France know anything about the region, they’ll likely cough up the old saying that “that's where they have more cows than people” – which may well be true, given that this is one of the most sparsely populated places in western Europe, with only 5-10 people per square kilometer.

It has achingly beautiful landscapes and vast open spaces. Its history is tied to some of the most interesting moments and movements in France’s rich past. True, I would never want specifically to live there (I’m a city boy! This place is the most rural place imaginable!) Despite its wilderness character, though, a visit to the Aubrac gets me quickly to the heart of why I think of “the deep heart of France” as my home away from home. Here are 3 reasons why I’m so attached:

(1) “It’s not just a job, it’s an adventure” (and a discovery that is 100% our own)

When we first moved to France in 1998, we were making a conscious choice to integrate ourselves into a language and a culture completely different from our own. My company wouldn’t fund an exploratory trip before we moved to Clermont-Ferrand, so the only information we had came from a very slim paperback about the Auvergne that I found in a Dallas bookstore. (Google had not gone live then, there was no list of “Top 10 Things to Do” on TripAdvisor, no website for the Office of Tourism in France.) The stories it told about the region’s deep history and natural beauty were attractive, but they weren’t the deciding factor for us.

I had been doing international IT projects for a while – opening new factories in Switzerland and China, deploying a marketing system in Taiwan, and setting up a huge warehouse in Moscow. But those seemed more like “IT tourism”, dropping in with my team to a foreign setting for 3 or 4 weeks at a time; I knew I loved this aspect of my job, but I also knew I would never truly internalize another culture unless we got ourselves immersed in one. And more than anything, I wanted to prove to myself at mid-career that I could still master something that was not directly linked to my technical skills in IT.

We loved the experience! My son went to the international school in Clermont-Ferrand and learned French at an incredible rate; Karen got involved with several different expat groups and elevated her French to the level of playing bridge with a group of local women and navigating the bureaucracy at the post office. At work, I was one of only two Anglophones in the company’s core IT leadership team. There weren’t any English-language bookstores or American movies in Clermont, so when we needed a quick fix from back home we had to catch the train to Paris for a weekend.

And we learned everything we had to know almost entirely through our direct experiences of the people and places we encountered in France. We discovered the country for ourselves and made it our own – experiencing it “unvarnished and unprocessed”, in the neat phrase Seth Kugel uses in his wonderful book, Rediscovering Travel: A Guide for the Globally Curious. Life in France became a routine part of our life – so much so that Karen and I moved back for a second expatriation several years later, and I spent most of my days in between those two periods on the phone with my colleagues in France or traveling back to Clermont for in-person meetings.

In our drive to discover France for ourselves, we used our weekends and every day of our extended French vacations to drive all over the country, visiting castles and ancient churches, sampling regional cuisines, and absorbing this whole new way of life. Of course, we saw the obligatory big sights that every tourist checks off his bucket list – the cathedrals at Reims and Chartres, the Roman ruins at Arles, and the Louvre in Paris.

But the things we remember the most – the things we still tell stories about – came in the small, unexpected moments we experienced. I’m thinking of the sunny Sunday morning when one of my neighbors in Sayat invited me into his garage to share his homemade liqueurs and tell me about his experiences as a French sailor docking in New York’s harbor. I’m thinking of the afternoon I spent as the solitary visitor to a tiny 1-room museum devoted to the infamous “Beast of Gevaudan”; the volunteer caretaker, hearing my accent, spent 30 minutes giving me a VIP tour of the exhibits, then talked with me for another hour about the state of American politics and world events. I remember the Loire Valley winemaker who left Karen and me in his tasting room while he took our son out to the vats and let him drink raw grape juice from a hose, and I remember the colleague who invited us to a small-town café to hear him play with his Dixieland jazz band.

Seth Kugel has another neat phrase for this phenomenon: “meeting people around their passions”. Seen from this distance, I know this sense of discovery – the long process of developing a lasting attachment to a place by experiencing it without filters and making it your own – is absolutely at the heart of my feelings about France. And the bond is made stronger by the fact that we started down this road in mid-life, in the course of a technical career, and in a language other than our own.

My favorite author, John LeCarre, thought about this process, too. In The Pigeon Tunnel, his remarkable memoir, he writes about his own fascination with another country and another culture; in his case, it was Germany rather than France, but he says something about his life-long obsession with all things Germanic that particularly resonates with my feelings about France:

“It gave me my own patch of eclectic territory; it fed my incurable romanticism and my love of lyricism; it instilled in me the notion that a man’s journey from cradle to grave was one unending education – hardly an original concept and probably questionable, but nevertheless.”

(2) The Aubrac is a “landscape of the soul”

So what does any of this metaphysical sense of discovery have to do with a visit to the Aubrac? It’s an absolutely beautiful landscape, but we’ve seen lots of those in our travels. What’s different about this one?

Here's what is weird about my love for places like the Aubrac: I am 100% a city dweller. I like big cities and all the cultural, historic, commercial, and culinary benefits that come with them. I deliberately eschewed country life when I sold my interest in the farm we have had in my family for 110 years to my brother. And yet…every time I have driven through the Cantal (and its emptiest corner, the Aubrac), I’ve felt the same awe and emotional tug that others might see in the Grand Canyon or the sharp peaks of the Himalayas.

Neurologists and psychiatrists tell us it’s partly science – our brains appear programmed to respond in specific ways to the colors and sweep of a natural landscape. But a Nordic travel writer recently introduced me to a new word: silunmaisema – “landscape of the soul” in Finnish, “a place with the power to unlock your heart and stay with you, wherever you are.” For me, that’s the Auvergne in general, the département of the Cantal in particular, and most specifically the great plateau of the Aubrac.

(And by the way, this is a landscape with wildly different looks, depending on the season. I’ve never been tempted to try these narrow “D” roads in the winter, but these photographs give you an idea of how isolated and utterly beautiful this place must be during the harshest months of the year!)

(3) An empty wilderness can still be part of the great movements of history

There’s another side to this gorgeous landscape that appeals to me: even though it looks wild and eternally uninhabited, in fact it participated in some of the same historic movements that shaped modern France. Celtic tribes lived on the plateau 3,000 years ago; the Roman armies of Julius Caesar marched through the region.

It was for centuries a dangerous place for any traveler, with roving gangs of robbers and packs of wolves threatening anyone who passed. By virtue of its position on the major pilgrimage routes, the Aubrac became an important stopping point on the Route to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. In fact, the tiny little village named for the plateau arose from the intersection of those two facts: when the Vicomte of Flanders was attacked by brigands on his way to Compostela in 1120, he made a promise to God that he would build a hospital here for other pilgrims in need if he survived.

The vestiges of it are still here at one of the highest points on the basaltic plain. You can visit L’Eglise Notre Dame des Pauvres (Our Lady of the Poor), founded on the spot of the Vicomte’s original hospital and turned into a simple Romanesque church in the 14th century. Claiming to be the best-preserved site of its type, it houses a basin where pilgrims could have their feet washed and a 15th-century "bell for the lost" that was rung to help people lost in the vast wilderness of the Aubrac to find their way to the hospital.

Even more remarkably for a village this tiny, Aubrac features a UNESCO World Heritage site related to the Camino de Santiago de Compostela’s pilgrims: a small stone bridge, built in the 1300s and providing the only spot in this region where travelers could safely cross the Boralde River.

And in addition to the constant menace of roving brigands, another threat came to this part of the wilderness: the marauding English armies of the Hundred Years War. By the time of the war a whole Augustinian monastery had grown up around the pilgrim hospital, and when the conflict came to this part of France in 1353 they added a defensive tower to the complex to house the 12 knights who protected the village. It still stands at the village’s edge, alongside the restored church/hospital; the rest of the grand monastery and its walls were destroyed during the French Revolution.

Why the Aubrac means so much to me

Why does a place like the Aubrac have such a strong appeal to me? It’s obviously very beautiful, but it’s also obviously a harsh environment. As someone who grew up on and around a farm, I can appreciate the everyday challenges that make farming such a difficult way of life in this rocky, thin soil. My imagination of history is sparked by thinking about little bands of pilgrims making their way across the basaltic plain 800 years ago, dodging wolves and robbers and the armies of the English king. And even though my own preferences are strictly urban, I’m interested in what it must be like to live in such a small village so far removed from big-city “conveniences”.

But in the larger scheme of things, visiting the Aubrac has a much deeper meaning for me. It’s one stop on my 25-year journey to learn another language and master moving easily in another culture. It appeals profoundly to my life-long study of history and its consequences for our lives today. Above all, it is part of that process of personal discovery – of making a place my own through “unvarnished and unprocessed” experiences, as Seth Kugel puts it.

That’s my story. Is there a place on earth that makes you feel the same way? What do you think makes places like the Aubrac so appealing to travelers? Please share your thoughts and experiences in the comments section below. (And while you’re here, I’d be grateful if you could take a moment to share this post with someone else who is interested in the people, places, culture and history of “the deep heart of France”!)

Unless otherwise noted, all photos in this post are copyright © 2021 by Richard Alexander

I have a deep appreciation for rural France… we steer our shared Dutch Barge down the Canal du Nivernais for 3-4 weeks a year and enjoy the serenity of the vast fields of sunflowers, corn or pasture….to live there for a year would not satisfy my desire to assimilate into a culture so rich and peaceful… thank you for your newsletter Richard….Phil A

Thanks for your kind comment, Phil. Slow traveling through the canal network remains near the top of my bucket list; I’m glad you have the opportunity to do that! Thanks for reading.

I’ve enjoyed reading your story about how Aubrac appeals to you. I’ve also learned about a book (The Pigeon Tunnel) and a new word (silunmaisema) – thank you! I’d studied French in high school and visited France for the first time as a college student. I’d spent almost a month in the village of Hérisson (also in the Auvergne region, specifically in the Allier département). My group and I also visited Montluçon, Néris-les-Bains, Venas, Vieure, Le Brethon, and hiked through the Tronçais Forest! I fondly recall medieval castles and the area’s natural beauty. I appreciated the quiet and slow pace there. I look forward to reading more about your adventures and discoveries in the deep heart of France!

Bonjour Darlene. I’m glad you enjoyed this – and really glad to hear about your experiences in central France, too. Thanks for writing!

Dear Richard,

I’m glad that you are back. It’s always a pleasure to read your articles. I know very well the feeling of “silunmaisema” – “landscape of the soul” as I used to live in Kent, England.

All the best,

Judit Szabó (from Hungary)

Hi Judit. Thanks very much for your kind comments! It’s good to hear from you.

Loved reading this piece on the Aubrac, Richard. I would love to explore it a little more having read it. Please do get in touch next time you’re back in France!

It’s great to hear from you, Laurie! All our best to you and Lee!

Wonderful write up, thank you for sharing your passionate tie to this sliver of heaven. By any chance, would you know when the narcisse’ farms will be in full bloom in Aubrac? My soul landscape is where flowers bloom !

Merci

I know people who think these parts of France are ‘the boring bits’ of the country. But I am with you on this, Richard. It takes some sensitivity and an eye for the power of simplicity and the understated style and passion for the locality to get it, but there is an almost intangible, profound beauty to be found in such places if you look hard enough. Just the light, the little-known history and how it relates to what we see today, stories from the past that define a place, the joy in noticing the changing colours of the landscape demand an eye such as yours to really understand. And then the skill to pen it. You write with such an infectious passion which I totally get. Thanks for posting.

Thanks very much for writing! I really appreciate your kind words of encouragement!