On June 22, 1940, a somber caravan of cars and trucks arrived in Vichy, a spa town in central France. They brought with them the principal political luminaries and the mechanics of bureaucracy for what remained of the French government after the Nazi army occupied Paris. Eight decades later, the town still struggles to restore its image as one of Europe’s most historic luxury resorts.

In last week’s post, I talked about all the great reasons to visit Vichy in the deep heart of central France: it’s a resort town with a rich history, a UNESCO World Heritage site known for its amazing thermal spas, a city full of remarkable examples of Belle Epoque architecture and first-class recreational opportunities. On the surface it’s a great place to visit – but when you say its name, at least in some circles, the word “Vichy” evokes negative, even hostile responses. What happened to tarnish the reputation of this lovely, historic town?

A legacy stained by World War II

Several of the senior managers I worked with in Clermont-Ferrand actually lived in Vichy, 32 miles and an easy train ride away from the larger city. One of them casually mentioned to me, “Oh, I live in the old U.S. Ambassador’s house,” and it took me a second to process the reference to that dark period in World War II when “Vichy France” referred above all to the residence of a compromised, collaborationist government.

There really aren’t two ways to look at it: the Vichy regime, under Marshall Philippe Pétain, was a cooperative tool of the Nazi takeover of France. After the government signed its armistice with Hitler’s armies, it was allowed to reconstitute itself as the “legitimate” power responsible for France’s “Free Zone” (roughly the southern half of the country). Pétain, the great hero of World War I, was still seen as almost a godlike paternal figure looking out for what he perceived to be the best interests of his country.

But the actual expression of those “best interests” turned out to be authoritarian and profoundly cruel. For a long time, it was assumed that Pétain and his ministers were just going along with Hitler’s directions and executing them on his behalf; more recently, though, the evidence says clearly that the Vichy government had its own authoritarian agenda and carried it out brutally and vigorously without much encouragement from the Germans.

The traditional French motto of “Liberty / Equality / Fraternity” was officially replaced with the more ominous “Work / Family / Fatherland”. Jews, homosexuals, and other “enemies of the state” were rounded up and deported even without orders from Nazi overseers. French police forces were used to enforce German orders, to spy on French citizens, and to harass anyone who resisted the new order. Those who resisted too much were tracked down and executed on orders emanating from Vichy.

(If you’re interested in reading more about Vichy’s troubled legacy and how it is perceived today, The Guardian published an excellent article by Julia Pascal in 2002 recounting how even now the Far-Right party of the Le Pens influences the city’s will and ability to deal with its past. I recommend it!)

Can Vichy shed its “problematic” reputation?

That’s how the town acquired the lingering stain on its perception around the world. And people in Vichy clearly know how bad the image is. Julie Pascal quotes one shopkeeper: "Vichy. It's like a lead weight pressing on us. At least once a week I get asked by people who come into my shop about the Pétain years. They whisper as if there is some terrible secret." The fact that a Prime Minister of France would still make a cutting reference to the town’s past in 2020 (see part I of this post) speaks volumes about how the city is perceived.

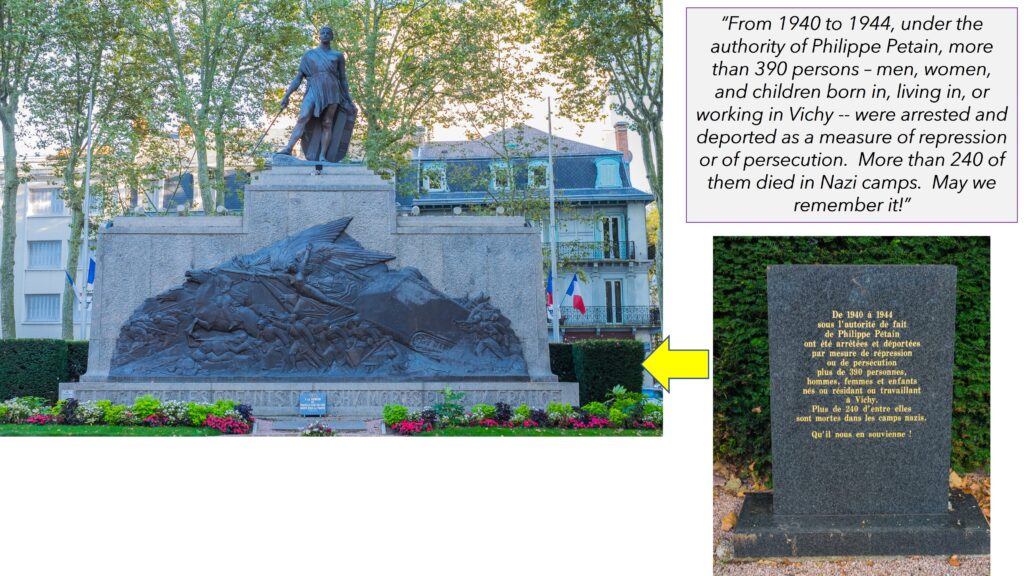

When you visit Vichy today, you can see one of the most elaborate war memorials to be found in any French city. It’s huge, and it lists the names of all those soldiers from this region who lost their lives in the two World Wars, as well as in France’s engagements in Algeria and Vietnam. But the only clue you’ll find to the darker episodes of World War II sits at the back corner of this monument, almost hidden behind a hedge; in generic terms (no names listed here!) it remembers 390 Vichy residents who Pétain’s government shipped off to Nazi prison camps, of whom 240 died there.

That little memorial is richly symbolic of Vichy’s difficulty in shedding its dark reputation, I think. It seems like too little – MUCH too little – and certainly too late. There seems to be no concentrated effort to confront the ugliness of Pétain’s regime, no meaningful acknowledgment of the damage it caused.

Julia Pascal’s article lists several other initiatives to clear the town’s reputation that have been considered and rejected over the years: a war museum, perhaps, or a research center devoted to the Resistance fighters who sought to bring down the Vichy regime. She quotes the local director of tourism: "A museum here is risky," he says. "It is something the Jews want, but this would be a monument to shame. We'd end up like the Pope, who apologizes for the Crusades and the Inquisition. The Vichyssois are humiliated by this past, they don't want to talk about it.”

The city has succeeded in some of its efforts to rehabilitate its image. The Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris has announced its intention to stop referring to “the Vichy regime” in future editions of its documents. The mayor of Aix-en-Provence has agreed to remove language about the Vichy government from its own memorial plaques. But these efforts seem more cosmetic than substantive – repeating the battle cry that “Vichy is a city! It’s not a regime!”

(Or, as the mayor of Aix-en-Provence says, “les Vichyssois ne sont pas les vichystes.”) Unless things evolve further in the current political climate – and unless the town can find ways meaningfully to confront its role in the Pétain regime -- it may still take more time before that stain is lifted.

So why come to Vichy now?

I hope you’ll understand why it’s taken me a while to wrestle this subject into words. On the one hand, the identification of Vichy with its ugly collaborationist history remains a constant in France’s political dialogue, even in 2021. On the other hand, the city does have another history that is rich and interesting in its own right – and there’s no doubt that it is a very attractive, comfortable, lively place to visit as a tourist.

So why come here now? My answer would be, “Come to ‘take the waters’, if that’s interesting to you. Come to admire the Belle Epoque architecture. Come to appreciate the long history that came before ‘that other history’. By all means, explore the visible links to that dark period of World War II and reflect on how that legacy has wormed into French consciousness and the political dialogue even now. But come, too, to walk through the great park along the banks of the Allier and come to enjoy the good life in the deep heart of France."

What have you heard about Vichy as a place to visit? Does the name still hold negative associations for you? Please share your experiences in the comments section below – and while you’re here, please take a second to share this post with someone else who might be interested in the people, history, places, and culture of central France.

Thanks Richard, whenever I visit Vichy or read about it in the WWII context, I always have similar questions which go unanswered. Thanks for exploring this in the two articles. Jake

Thanks for the comment, Jake – it’s great to hear from you!

I can see you are wrestling with this, Richard. And you are right, it is a complex issue, to say the least. But it did make me think about modern Germany and even Austria (as well as a few other occupied countries) and how many places must be in the same situation: of shedding their past horrors and collaboration with the Nazi occupiers. Surely it is time for Vichy, and more to the point, the rest of France to move on from this now and look for a future of peace and co-operation with Vichy. They should take the lesson from Nelson Mandela. I was fortunate enough to hear one of his former body guards talk of his time with Nelson Mandela. The former SA president put him in a collaborative position with the person who had tortured him under the apartheid regime as part of the peace and reconciliation philosophy. The reason was that Nelson Mandela believed that past injustices could only be healed by both sides agreeing to Peace and Reconciliation. And the result? The former white torturer is now godfather to the child of the former victim. This is what Vichy and the rest of France need to aspire to. But both you and I know how revenge sits in French history, I guess. Maybe it is not our place to comment, as non-French people. Sadly, I just did. Because I care. Work that one out.

I think you’ve captured precisely the difficulty I was trying to express – thanks for putting it so succinctly! Add to the mix the apparent attraction of some in French politics in 2021 for what they see as the “traditional values” of the Vichy regime and the whole question becomes even more complex. As always, thanks for a very thoughtful addition to the discussion!

You and the commenters have teased out the critical issues here. And I believe that it is past time for France and the world to acknowledge that the regime’s occupation of Vichy was unfortunate for Vichy, but the city should not be judged by those who took advantage of its location and beauty for their own evil purposes.

One of your photos reminds me of my children’s favorite Vichy souvenir – the mints! They’re classic.

Thanks for both your comments, Sheryl! We share some of the same memories, and I agree especially that Vichy’s parks and public places are great places for entertaining the kids. I agree, too, that were it not for the accident of history — the presence of all those hotels and meeting spaces that you might find in any other resort town — Vichy wouldn’t be saddled with its bad reputation. I think it’s the fact that they have had such difficulty confronting this past effectively that keeps the town trapped in this history. As always, thank you for reading — and thanks for taking time to comment!

Being in region for a while now, friends often recommend places nearby to visit, Riom, Issoire etc but Vichy was never mentioned. On the spur of the moment I decided to pay a visit as it’s only 30 minutes train journey from Clermont. I had a great day exploring the city. Loved the parks and the riverside walk in perfect weather. An elegant city! Spent much longer than originally intended. I will definitely go again.