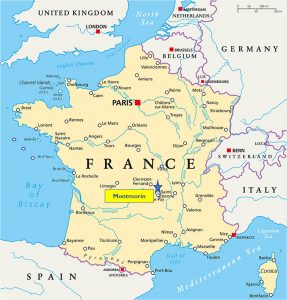

Somehow my visit to the crumbling castle ruins at Montmorin feels more important to me than the site itself really warrants. From the peak of this ancient little volcano, you can see forever – or at least that’s how it seems to me on a particular August afternoon in the deep heart of France. The entire Chaine des Puys, that iconic 25-mile-long range of extinct volcanoes that dominates the country’s center, is visible along the horizon to the west. As it happens so often in my travels through this region, I feel like the only person left on earth after some global cataclysm. I’ve come to visit the Chateau de Montmorin, a jumble of ruins at the end of a dangerously narrow “D” road, and there’s no one else in sight for many miles around.

Why do I feel something out of the ordinary on this specific afternoon? How could a place so pedestrian, so shambolic, remind me of so many of the themes I’ve written about over the years? I have some time to reflect; the castle was supposed to open at 2:00, and it’s now 2:40. The massive wooden entry is locked tight, although the signs clearly say the place is open for tours. I sit on the hood of my car and wait, meditating on the terrain sauvage and listening as the distant sounds of a motor draw closer. At last, a car emerges (coming the wrong way up the side of the mountain) and a young woman fumbles with her keys to open the door.

A castle in ruins and the project to bring it back to life

“Je suis vraiment désolée,” she says, explaining that an accident on the little road had blocked traffic in every direction. I’m the only tourist here this afternoon, so I am treated to a completely personalized tour of the ruins. And “ruins” is really the only way to describe the site; although a couple of “whole” buildings remain, from many angles the old castle looks more like a pile of rocks struggling to hold itself together in some recognizable form.

As my guide and I walk into the courtyard, though, other cars are arriving – the castle’s work crew coming back from lunch. They are hoisting buckets of sand to make mortar, levering huge stones into place, laying down a new floor in what remains of a kitchen, all to bring Montmorin back to life.

It’s a labor of passion for the site’s current owner, Philippe Dubus. He has undertaken this restoration, my guide tells me, with no historical records to guide the work – no surviving plans, none of the antique paintings or gravures that are available for so many other French chateaux. He also faces challenges that other builders never face, including the fact that thousands of stones have been carted away over the centuries and used to build other peoples’ houses. And because it’s a minor castle in the overall scheme of French history, far from the beaten path for tourists, there's not a flood of Euros coming in from visitors to finance what is essentially an open-ended project with no completion date in sight.

That, I think, is the first reason Montmorin affects me so deeply: it is in many ways a mad venture, driven entirely by love for the region and the history this place represents. I’ve encountered some other sites sustained by similar passions – the ruins at Polignac and the rugged fortress at Murol for example, or the incredible “gated community” of the Chateau de Commarque in the Dordogne. But those places are better-known, closer to tourist destinations – they are bigger and more “reasonable” in their ambitions to attract visitors. I find myself enthralled as my guide tells the story and digs into the details of all the heavy restoration projects that remain to be done “someday.”

There is an “Association of Friends of Montmorin” to aid the work, but even their appeal for support on the Chateau’s website struck me as extraordinary:

“For 200 years, this exceptional place served as a quarry for the construction of other buildings; it slowly disintegrated… Today, we have an idea, a dream (perhaps a little out of touch with reality): to reverse this process of decline. So we’re calling on your generosity. We accept with pleasure all gifts of stones…The chateau gave for a long time; it does not want in any case to retake, but to receive. Creating a sufficient stock of stones will permit the reconstruction of the ramparts. It would offer a new dignity, a new armor, to that which watched over and still watches over the village of Montmorin.”

The rise to power begins at home

This idea that the Chateau de Montmorin “watches over” everything it surveys is highlighted in the remarkable story of the castle’s past. The first known building on the site was constructed around 950 C.E.; the buildings that now stand here in ruins were started in the 1100s and expanded over the centuries.

My guide relates the story of the long rise of the Montmorin family to become one of the most powerful families in the Auvergne. A statue of a knight named “Calixte” on the castle grounds says he was in Jerusalem for the First Crusade to Jerusalem in 1096, although online sources suggest his name was “Roger”. In 1147, Hugues III de Montmorin signed up with King Louis VII to go off on the Second Crusade (which didn’t end that well for the Europeans).

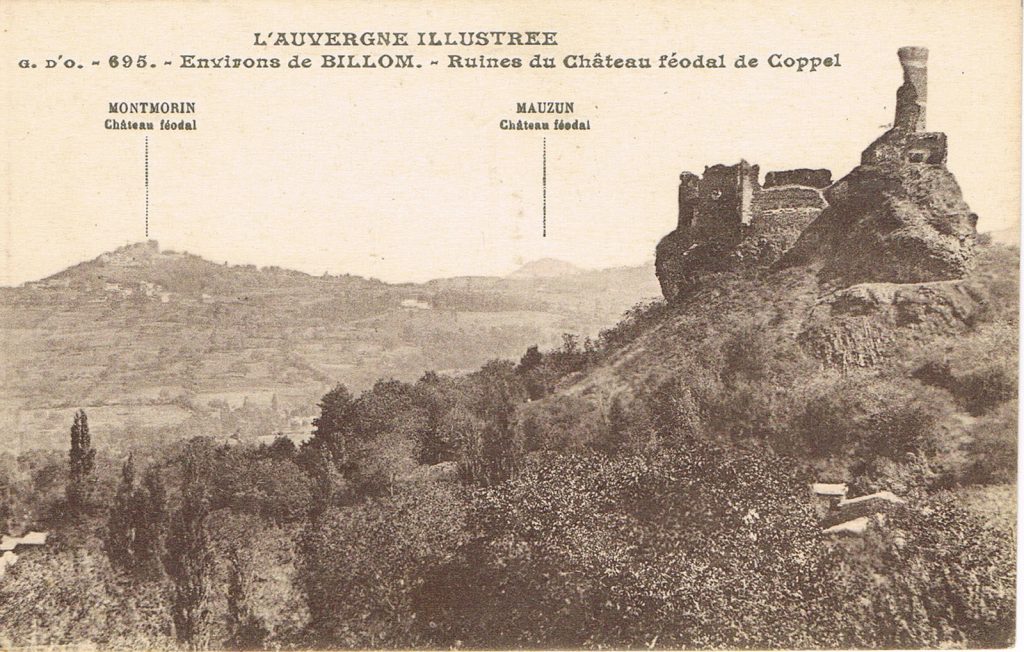

Even more remarkably, though, the family used its skills in diplomacy and negotiation to reinforce its reputation over the centuries – and you can still see the evidence from the high point of these ruins. My guide points out two other ruined castles, the Chateau de Coppel to the southwest and the Chateau de Mauzun to the northeast of where we’re standing. (Google says you can walk from Coppel to Montmorin in an hour; the walk from here to Mauzun is two hours. I drove the whole distance that spans the three in less than 30 minutes.)

Coppel belonged to the Counts of the Auvergne, the powerful family dedicated to perpetuating its influence independent of the Kings of France. Mauzun was built by those Counts, too, but taken over by the Bishop of Clermont, whose close ties to the King essentially made him an archenemy to the Coppels. According to my guide, that left the Montmorins to shuttle between their two contentious neighbors, arranging marriages and otherwise acting to preserve the peace in the region for much of the 13th century!

From the wilderness of Montmorin to the international stage

The family’s power continued to be evident as the centuries passed. When Cardinal Richelieu was busy in the 1600s destroying 2,000 defensive castles all across France, helping Louis XIII concentrate his power as king, he spared Montmorin because of the family’s close ties to the monarch. Symbolic of this power, those other nearby castles – Mauzun and Coppel – were not spared and were razed to rubble during the campaign.

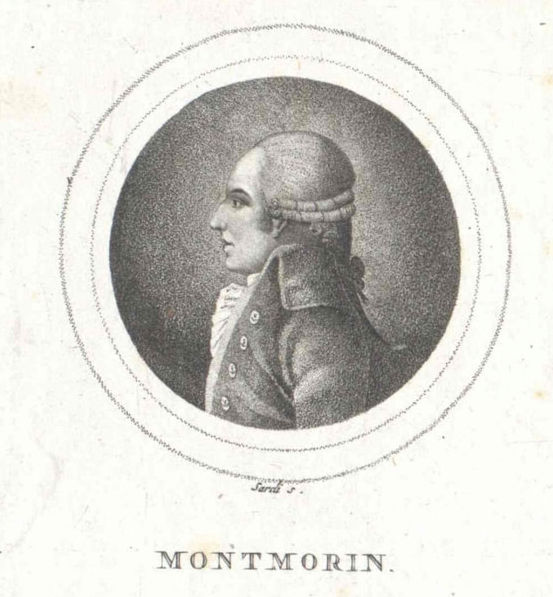

And then…my guide tells me the extraordinary story of Armand Marc, the 18th-century Count of Montmorin. This whole discussion led me to a second reflection on why Montmorin affects me so deeply: the stories of people who rise from remote, wilderness corners of France to become powerful actors in the history of their times. Joan of Arc is one such familiar story; I’ve written about how the Marquis de Lafayette left his rustic home in the south to become a key player in the American Revolution, and about how a young monk ascended the hierarchy from his humble beginnings in the abbey at La Chaise Dieu to become Pope Clement VI. These stories fascinate me – what elements of their character, what work habits, what powerful ambitions drive people like this onto the world stage?

Armand Marc was actually born in Paris in 1745, already a step up for an isolated “junior family” of the nobility. He became first a gentleman-in-waiting to the future king when Louis XVI was only 7 years old, then (when Louis took the throne) Armand was appointed French ambassador to the Spanish court in Madrid. In that role, he showed that he had inherited his family’s capacity for diplomacy by persuading the King of Spain to send help to the American Revolutionary armies. (How, exactly, do you persuade a king that it’s a promising idea to overthrow a monarchy?)

The Count was one of Louis XVI’s chief advisors – the King’s “bras droit”, as my guide puts it – when the French Revolution boiled over. (He was so close to the King that he signed the passports that Louis and Marie-Antoinette used in their aborted attempt to escape from Paris.) Armand tried diplomacy one more time, trying to work as an intermediary between the King and the revolutionary leader Mirabeau. When that failed, Armand was eventually tried by a revolutionary court, sent to prison, and killed there during the September Massacre of 1792.

Touring Montmorin today

There’s a small museum at the end of our tour – the Musée Henri Delaire (named for the man who started the first restoration project here in 1965), with four rooms of archeological artifacts, antique armor and weapons, and old tools. We walk back outside to the highest point of the castle site, looking out across the great Plain of Limagne to the Chaine des Puys, and I’m reminded again of the third reason I love (and write about) this part of France: it is absolutely gorgeous! Except for the little village at the base of the hill, the area is so wild and sparsely populated that it is easy to imagine how it would have looked to a medieval traveler seeking shelter here in 1250.

The young woman guiding me is quiet for a while, too. Like me, I think, she may know that the history she has just narrated for me is probably more interesting than the crumbled ruins around us. I know, too, that you’re never likely to see the Chateau de Montmorin in person anytime soon – it’s still too small, too remote from anywhere you’re likely to be, and (for now, at least) just too “ruined” for me to recommend it in good conscience as a destination. I’m writing about it here for the feelings that well up when I reflect on what it represents. This incredibly old castle is an intensely passionate restoration project, driven by the certainty that great events on the world stage were shaped by the people who once lived here. It has a past that matters, and it is set against the backdrop of one of the wildest, most beautiful regions of central France.

All these elements made this a special afternoon visit for me. I’d be grateful to hear what YOU think – do you have a place that raises similar feelings for you? What makes a site special to you – the history? The landscape? The architectural interest? Please share your experience in the comments section below, and while you’re here please take a moment to share this post with someone else who loves the people, places, culture, and history of the deep heart of France!

Wow. This is well done history. Really interesting.

Thanks very much, as always, for your very kind comment!

Merci de ce joli texte. Merce de vos commentaires,