If you’ve followed this blog, you know I have a longstanding fascination with people who come from difficult beginnings in remote parts of the country and somehow forge a national reputation and a lasting place in history.

It’s not that I follow the “great man” school of historic thought – I don’t! – but many of these people just have personal stories that are so compelling they are worth knowing about. Joan of Arc is certainly a prominent example in French history; in this space, I’ve written about Lafayette (hero of both the American and French Revolutions), about Pope Clement VI (a monk from the remote abbey at La Chaise-Dieu), and about the Count of Montmorin (Louix XVI’s “right-hand man”), all of whom rose from humble origins to leave a mark on the history of their country or the world.

The country roots of General Desaix

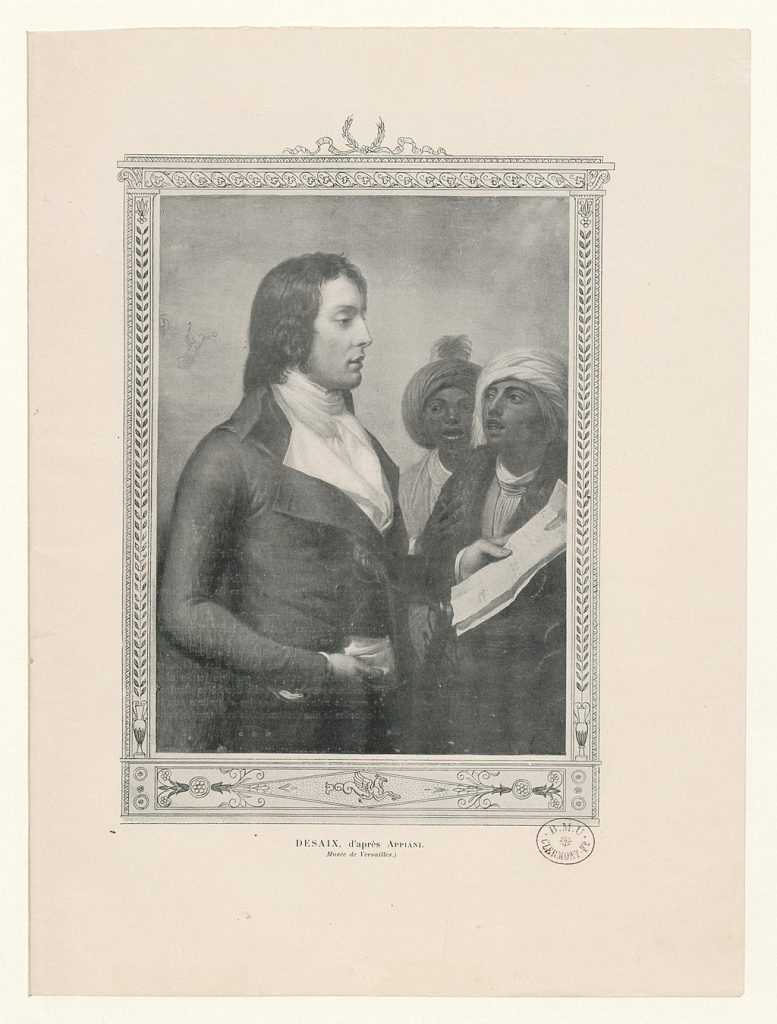

This, then, is the story of another national hero, one of the most famous generals in the time of the French Revolution: General Desaix -- or, to give him his full name at the risk of overflowing his business card: Louis Charles Antoine Desaix. (In this part of the country, they pronounce the family name as ‘DEZ-AY’).

As that name implies, Desaix came from a “noble” family, but you shouldn’t imagine that he grew up in one of the miniature palaces or even one of the minor castles that are found throughout central France. His birthplace, the Manoir de Veygoux, is technically a “chateau” because of the status of the family that lived in it, but in almost every respect it is a modest country house, far from the nearest settlement of any consequence. This is territory far from Paris in every possible dimension, and Desaix was the third son, born in 1768, of a family far removed from the well-connected nobles that populated the royal court of Louis XVI.

Given his place in the overall scheme of French society, it was not unusual that Desaix was sent away at the age of 8 to a Royal Military School at Effiat, not far from his home. Apparently, he did well there; he was a sub-lieutenant by the age of 15. But these were turbulent times. When the French Revolution began in 1789, Desaix was 21 years old. Most of his family remained loyal to the King, and when they decided to escape the country in 1792, he had to make a hard choice: Desaix stayed in France and joined the conflict on the side of the revolutionaries.

A natural military leader

Although he was reportedly “shy and polite”, he must have had leadership skills that were evident to those around him (and to the Republican government in charge at this stage of the Revolution). Desaix was a captain in the Army of the Rhine by age 24. When he was 25, in an extraordinary sequence of events, he was promoted to battalion chief, shot through both cheeks during a battle at Lauterborg, promoted on the battlefield to brigade general, then only two months later to division general! He led a division that drove the Austrian army out of the forest of Bienwald.

Even that record of success did not insulate Desaix entirely from the white-hot political volatility that characterized Revolutionary France. Despite his miraculous advancements in 1793, someone in command thought he should be suspended and prosecuted for being associated with a family of royalists. Apparently better military minds prevailed because the orders for his suspension were never carried out.

Desaix’s battlefield successes against the Austrians multiplied over the next four years, and when that conflict ended in 1797, he was invited to Italy to meet another general: Napoleon Bonaparte (himself no slouch in the history of “people who rose to great heights from humble origins”!) Desaix joined Napoleon’s forces for the massive “Expedition to Egypt”, and he personally led the part of the campaign responsible for “pacifying” all of Upper Egypt. He did win the battles, but he was also apparently a fair administrator of the territories he conquered; many Egyptians called him “the Just Sultan” for his contributions to improving the quality of life in the region.

Desaix remained in the service of Napoleon’s Grande Armée when he returned to join Napoleon’s campaign against the Austrians in Italy in 1800. In a battle there (at Marengo) on June 14, 1800, he was shot through the heart by an enemy bullet and died on the field.

Napoleon Bonaparte clearly recognized Desaix’s contributions to his military campaigns, putting up two monuments in his honor in Paris and writing his name on the face of the Arc de Triomphe. But his legacy is still celebrated all over France: a statue in his honor stands in the central square of Clermont-Ferrand, there’s a cenotaph in Strasbourg and a fountain in Riom. Several French cities have boulevards named in his honor, three French forts bear his name, and a couple of French battleships were named Desaix over the past two centuries. (And his reputation spread to France’s former territories – you can still find “Desaix” streets in Detroit and New Orleans, a Desaix Island in Australia, and similar homages in places like Algeria, Tunisia, and Sudan!)

Visiting the Manoir de Veygoux today

I arrive at the Desaix ancestral home on a bright, cool afternoon, with the wind pushing sharply across the volcanic plain. I have not seen another car on this road for the last 15 minutes, and when I get to the Manoir’s parking lot there are only 3 other vehicles in the lot. (Strange, I think, that a place of this historic interest is so lightly visited compared to the 1,000+ cars I saw in the lot at a tourist destination like Vulcania, just 12 miles from here!)

The Manoir de Veygoux has been extensively restored in recent decades, with the barns and outbuildings turned into well-curated displays about the history of the French Revolution and Desaix’s place in the pantheon of revolutionary figures. One of the most interesting panels lists other famous Auvergnats who contributed to the foundation of the Republic – there’s the Marquis de Lafayette, of course, but also:

- Jean-Francois Gaultier, the first Republican mayor of Clermont-Ferrand;

- George Auguste Couthon, who argued for the Terror alongside Robespierre and who went to the guillotine on the same day as his mentor; and

- Pierre-Amable Soubrany de Macholles, who tried to stab himself before he could be taken to the guillotine; he survived the attempt but died in the wagon on the way to his execution, so he has the distinction of having had his head cut off after he was dead!

You can tour the house and grounds of the Manoir de Veygoux wearing a period costume if you want – they have racks available for rent in the ticket office and gift shop, although none of the visitors have taken advantage of the offer while I am here. The interior of the house, though, certainly lends itself to imagining yourself in another time and place. Like some of the best French tourist attractions we have visited, it is authentically decorated as it might have been when Desaix grew up here – a plain country house with big, comfortable rooms and a well-stocked library.

And the house itself tells the family’s story, with voices speaking from illuminated portraits to relate how divided the people became over the demands of the Revolution and how Desaix fit into the picture. There are interesting “animations”, too – drawers that open and close during the narration, the sounds of footsteps from the floor above, and the sounds of chains dragging, all adding to the effect that you’re seeing how the family might really have lived here.

Leaving Desaix behind

In the end, a visit to the Manoir de Veygoux does not necessarily answer all my questions about how someone like General Desaix – the third son of a minor family in the deep heart of France – found a place on the world stage. It goes a long way, though, showing how a boy like this could rise on the strength of his personal skills as a quiet, calm leader in a time when chaos was the rule of the day in French society. The exhibits here help position his life in the context of the great movements of the Revolution and Bonaparte’s conquests. Most importantly, they tell a coherent, compelling story of how Desaix made his way through the world and made the most of the opportunities he encountered along the way. And for me, that’s answer enough for now.

Have you visited any other site in France associated with the rise of a notable person in history? What did you appreciate about it? Were you able to learn anything about how this kind of success was possible? Please share your experience in the comments section below. And I would be grateful if you would also take a moment to share this post with someone else who is interested in the people, places, culture, and history of the “deep heart of France”!

Unless otherwise noted, all photos in this post are copyright © 2023 by Richard Alexander

Once again, your in depth research has given us some gems of information. Thanks, Richard.

Interesting and informative post. On his deathbead and while delerious one of Napoleon’s final words was “Desaix.” Perhaps he was recalling Desaix’s timely arrival that won the Battle of Marengo and thus propelled napoleon to even greater heights of glory.

Very interesting – I had never heard that! Thanks for sharing this.