The celebration is finally here!

It’s official: Clermont-Ferrand has just launched its year-long celebration of the 400th anniversary of the birth of Blaise Pascal, “le génie Clermontois.” The party started earlier this month with a performance of music from Pascal’s lifetime in the lovely church of Notre Dame du Port. Over the next 12 months, the celebration continues with:

- Exhibits at the Henri-Lecoq museum of science and natural history and the Roger-Quilliot museum of art

- An online collection of documents at the Overnia (Clermont's digital library of historical materials) about the great man’s life, as well as reproductions of his most famous books and essays

- A year-long series of concerts, films, lectures and roundtables featuring distinguished artists and scholars celebrating Pascal’s life and the lasting impact of his work on the 21st-century world, leading up to an 11-day "Festival of Science" in October

There is even a plan (coming in April) to use Minecraft to build a video-game reproduction of the house in which Pascal was born at the foot of Clermont’s famous “black cathedral”. And in June the city’s Office of Tourism will host the launch of a new commemorative stamp celebrating Pascal’s life and work.

But why all this fuss over a man who died in the 1600s at the age of 39? Well, in that brief life span, Blaise Pascal produced seminal works in mathematics, applied engineering and meteorology, and computing. His thinking was so original and astonishing, even at the age of 16, that Descartes thought he must be a much older man. And his passionate immersion in religious philosophy as he got older produced some of the most profound and lasting debates in the history of Western civilization.

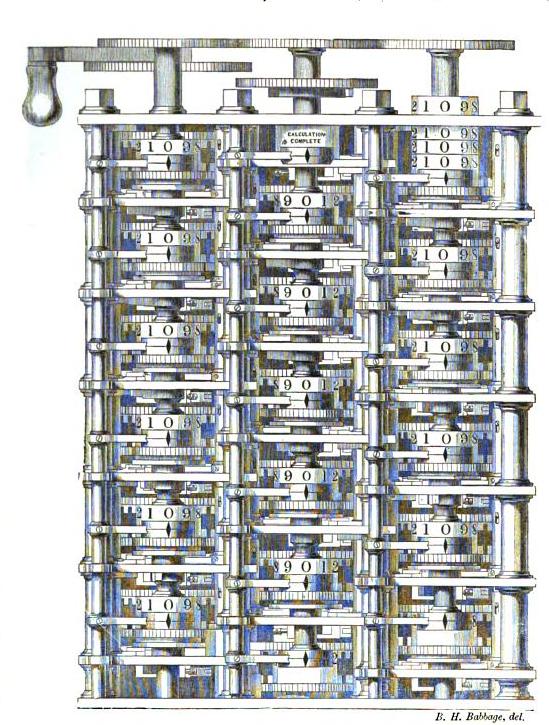

Babbage impressed the Queen – but Pascal was ahead by 200 years

A couple of years ago, Karen and I watched Season 2 of Victoria, the biographical series about England's Queen Victoria, on Amazon. One of the episodes was especially interesting to me: in it, Queen Victoria’s husband (Prince Albert) gets tremendously excited from meeting Charles Babbage, inventor of a great mechanical “difference engine” designed to perform complex calculations.

The episode also introduced Lady Ada Lovelace, the woman credited with devising the first programming language. Now I’m a “computer guy” by profession, so I knew the story of how these two are considered to be the 19th-century founders of modern computer science.

Celebrating 400 years of a "great genius of humanity"

But I’m also a Francophile by avocation, and I lived in Clermont-Ferrand for enough years to know that Blaise Pascal anticipated Babbage’s invention by 200 years. His “Pascaline” machine could add, subtract, multiply and divide, and was good enough to be used in his father’s tax office; Louis XIV gave Pascal a royal “privilege” entitling him to make and sell the machine anywhere in France. And he built it…when he was 19 years old!

The Museum of Arts and Métiers in Paris has a whole case full of examples, many of which are "verified and signed" as originals by Pascal himself. For someone who has only seen them in pictures, it's a great moment to stand in front of the collection; for anyone who's worked in computing or business information systems, this is one of the great leaps forward that made our profession possible.

And now, the city of Clermont-Ferrand is celebrating the 400th birthday of this native son and to remind everyone of Pascal’s roots in the Auvergne. It's not the first party they've organized for him: for the 300th-anniversary celebration in 1923, the President of France and several of his ministers came to Clermont to remember “one of the greatest geniuses of humanity at the level of Archimedes, of Galileo, of Newton, of Darwin, of Pasteur, or of Einstein,” as one of the national newspapers said at the time.

A genius in many fields

The incredible thing about Blaise Pascal is… well, for me, almost everything. He was one of those extraordinary intellects who come along too rarely in history, but like Mozart, like Shelley and Keats, he died before he turned 40, leaving us to wonder what else he might have done if he’d lived longer. (As the same national newspaper said for the 300th anniversary in 1923, "There was a kind of injustice...Pascal was born too soon. If he had been born two centuries later, he would have invented more. He just didn't have the tools...")

I first encountered him when, as a young professor of computer science, I was asked to teach a class on “Pascal”. In the 1980s it was a new, structured language for computer programming, a predecessor to some of the languages still used to write code.

It turned out that this very modern programming language was named for the 17th-century scientist and philosopher because, among his other inventions, he built that first real commercially distributed calculating machine in 1642. But the bigger picture is that he was involved in an incredible number of other fields of science and philosophy: fluid mechanics, geometry, probability, and Christian theology. And in several of them, he corresponded with the greatest thinkers of his age and developed theses that remain part of the bedrock knowledge of these disciplines in the 21st century.

Interested in knowing how the Pascaline works? Here's a 10-minute intro!

A true son of the deep heart of France

Pascal was born in Clermont-Ferrand in 1623, and although he moved away at an early age he considered himself a true Auvergnat, a child of the “deep heart of France”, and he came back several times during his life. He did his ground-breaking experiments on barometric pressure with his brother-in-law in Clermont-Ferrand in 1648 by comparing how tubes of mercury behaved in the city center and up at the summit of the Puy-de-Dome volcano.

Despite the diversity of his interests in physical science, his real genius was in mathematics. He read Euclid’s Elements at age 12, got admitted to regular conversations with some of France’s leading geometricians at 14, and published an essay on conical sections at 16. His exchange of letters with Fermat in 1654 is considered by those more mathematically literate than I am to be one of the building blocks of modern probability theory.

But something remarkable happened late that same year when Pascal had an overwhelming religious vision – a vision that shook him loose from the Jesuit training he’d grown up with and led him down the more radical path of Jansenism . He began to write – and just as his work in math and science is still considered to be “foundational”, his work as a writer still puts him in the top ranks of French thinkers 350 years later.

To cite a couple of examples: Pascal’s Pensées is not even a “complete” work – it’s more a collection of fragments and short pieces published after he died – but it is still a passionate, brilliantly-written defense of the faith he came to feel so intensely. (I can’t do justice to it here – if you’re interested, you can find an English translation with an introduction by T.S. Eliot here .)

He’s also famous for the proposition, famous in Christian thinking, that came to be known as “Pascal’s Wager”: “Granted that faith cannot be proved, what harm will come to you if you gamble on its truth and it proves false? If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing.”

There aren’t many traces of Pascal left in Clermont-Ferrand, other than the medallions with his name and face embedded in the cobblestones all around the centre ville. The medieval house in which he was born stood next to the famous “black cathedral” and was torn down in 1900 when the Place de la Victoire was cleared out to give a clearer view of the great church. (The front entry to the house was saved, though, and can still be seen in the Jardin le Coq park in downtown Clermont-Ferrand.)

A final "trace" of Pascal in Paris

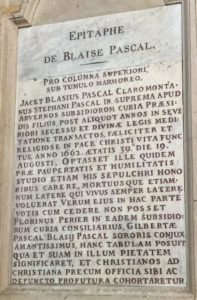

On our last visit to Paris we saw another place, new to us, that also has a connection to Blaise Pascal: the fine old Church of Saint-Etienne-du-Mont, next to the Pantheon on the Left Bank of the Seine. With its roots in the 6th century, it was updated repeatedly over the centuries. Two of the most important figures in the whole history of Paris -- King Clovis I (the first king of "all the united Franks") and Saint Genevieve (patron saint of the city) were both buried in the original building on the site. Margarite de Valois -- the notorious "Queen Margot" -- was present for the laying of the cornerstone of the west facade in 1610...

...and Blaise Pascal was buried here in Saint-Etienne-du-Mont when he died (apparently of stomach cancer) in 1662, not long after his 39th birthday. You can see the epitaph from his tombstone preserved in one of the church's walls. My high-school Latin is rusty, but (with some later help from Google) I was able to make out the honors paid to him as a man of "desire and zeal" who nevertheless managed to live in great piety and humility, a man who searched out the truth wherever it was hidden -- and a man with deep roots in the heart of France.

A life like no other

I’m frankly in awe of the intellect and energy that Pascal displayed in his short life. Like Mozart, Pascal produced a volume of work that would be dazzling in someone who lived to be 90. I see a modern-day parallel in Andrew Pinsent (the Catholic priest who’s also a physicist working on the Large Electron-Positron Collider at CERN); like Pinsent, Pascal could reconcile scientific methods with a spiritual vision of the world. And like me (in this respect, although in absolutely no other!) he came back frequently to the deep heart of France for inspiration and renewal.

Have you encountered Pascal in any of your professional pursuits? Can you think of anyone else who had such a broad vision of the world? Please join the conversation by adding to the comments section below. And please take a moment to share this post using one of the social-media buttons that follow.